Giallo

Live Radio Drama

Production: E / Fanny & AlexanderCo-production: AREA 06 - Short TheatreIn collaboration with: Solares delle Arti – Teatro delle Briciole

Creative Team

- Concept: Luigi De Angelis and Chiara Lagani

- Dramaturgy: Chiara Lagani

- Direction: Luigi De Angelis

- With: Chiara Lagani

- Voices: Alfonso Cafaro, Bassirou Fall, Anna Benini, Francesca Benini, Noemi Cicchetti Ferrante, Erik Cicchetti Ferrante, Nell Danesi, Nicolò Montanari, Pietro Lorenzo Spurio, Annagiulia Valgiusti, Federica Valzania, Sara Vernocchi, and other children from the “Pianeta Giallo” workshops (Parma and Ravenna)

Technical Team

- Model Design: Nicola Fagnani

- Sound Project: The Mad Stork

- Recordings: Marco Parollo and Sergio Policicchio

- Sound Editing: Sergio Policicchio

- Translation and Subtitles: Sergio Carioli

Production Support

- Organization: Serena Terranova and Filomena Volpe

- Promotion: Paola Granato

- Logistics: Fabio Sbaraglia

- Administration: Marco Cavalcoli and Debora Pazienza

Special Thanks

Beatrice Baruffini, Selina Bassini, Alessandra Belledi, Anna Maria Bollettieri, Roberta Colombo, Marilena Palmieri, Francesca Proia, Anna Zavatta.

“Would you believe it? This butterfly has one yellow wing, the other blue.” (T.S.)

GIALLO is a mysterious and ghostly radio dialogue between a shifting teacher figure and their invisible class. It explores the nature and form of the childlike part within each of us—hidden, radiant, furious, incandescent, remote, or buried.

Year : 2012 & 2013

Giallo: Discourse and Radiodrama by Fanny & Alexander

By Andrea Pocosgnich, teatroecritica.net, September 17, 2013

Yellow is the dominant color theme in the second chapter of Fanny & Alexander’s experimentation with “speeches.” After Discorso Grigio, where Marco Cavalcoli challenged political language, in Giallo, which seems to contradict its own sunny nature by turning into a deep darkness, Chiara Lagani showcases her extraordinary acting skills in a double project intertwining, across two major themes, television and education. The quintessential mass medium is linked to a reflection on teaching and the transmission of knowledge. At Short Theatre 8, the audience had the opportunity to attend two performances, differing in style and dramaturgy, which nonetheless represent a single, complex fresco, shattered into a myriad of fragments.

The diptych demonstrated the value of a profound and complex research process, despite the “draining” moment that some of the new Italian theater research faced here at Short Theatre. While some groups from the younger generations are focused on finding new devices that strip the staging of any protagonism by sharing the stage with non-professionals, people with disabilities, and children, the persistence of the Ravenna-based group manages to sidestep that risk—often leading unintentionally to winking at the audience—and rests mainly on a depth of thought that, at least in these two trials, does not create fractures between the device and the themes.

It is a complexity that undoubtedly requires a level of attention that the audience may no longer be accustomed to, but in both works seen at La Pelanda, the stimuli are multiple, and the rational logic with which we are usually accustomed to addressing fundamental issues such as education and communication is put at risk by something that escapes reason, urging dark visions of the unconscious.

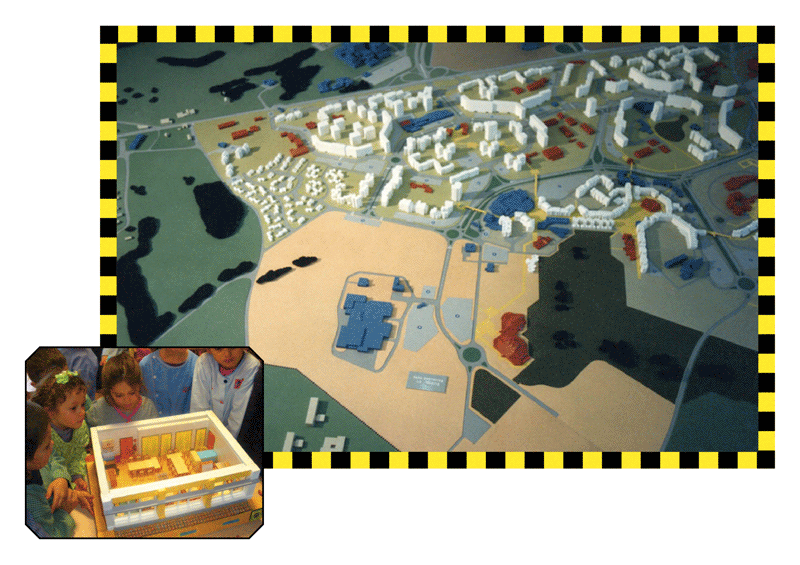

In the radiodrama—built from several workshop sessions—Chiara Lagani dialogues with the pre-recorded voices of a group of children. The sound design surrounds the spectators, seated on three sides of the stage, and at the center, a small wooden building, perhaps a school, is placed. The construction is empty, essential, lacquered in black and illuminated from within. The soft light of a desk lamp carefully controls the degree of visibility offered to the audience. The roll call is directed at us—we are those children, so the disorienting game of the sphinx/Lagani, who is both a teacher and a mysterious officiant of an unconscious ritual, is aimed at us. The voices of the young students ask to go to the bathroom, but we are not in the middle of a lesson: “I brought you here because I have a problem. I was in a forest, I met a creature, it was wounded.” The simple narrative spreads, sliding through the iterative folds of a dialogue, sometimes logical, sometimes disconnected, full of repetitions; then from the darkness emerges a figure, a monkey mask that tests the curiosity of the children. They are afraid but attracted, and one of the small voices states, “Don’t be afraid, it’s theater.” To not be afraid, the beast must be educated (and thus welcomed), taught to speak.

The element that also appears in Discorso Giallo is precisely the theme of education (and thus submission) which takes the form of a gigantic mask of Maria Montessori, an unsettling symbolic icon. However, Fanny & Alexander’s frantic performance, decidedly more physical than the previous one, also represents a dreamlike exploration of educational television: figures such as Maestro Manzi, Sandra Milo, and Maria De Filippi are intercepted within the same flow. Because, while the chronological line initially separates the three phases, as the performance progresses, the interferences accumulate and overlap in disorienting collisions that find their representation in the gestures, face, and voice of the performer, the mask of representation that the recursive dramaturgical mechanism—written by Lagani herself—requires.

By the end, the audience leaves tired, disoriented, with many questions and fortunately few answers, but with the awareness of having been the terminal point of a crisis not only of fundamental themes for our cultural system but also of the way we approach these themes.

SPECIAL SANTARCANGELO 13. The Childhood of Radio, Childhood of Theatre

By Nicola Villa, minimaetmoralia.it, July 30, 2013

The case of the Santarcangelo Festival, the theatre in the square, is unique: it is an international research theatre event, one of the longest-running in Italy, now in its 43rd edition, that not only addresses theatre and its branches but is also always attentive to the vitality of other contemporary arts, attempting to contaminate languages as much as possible. Those who have attended over the years were not surprised, then, that this year a mini-festival was dedicated to two themes seemingly distant from theatre: radio and childhood.

“Radio and Childhood,” the title of the project curated by festival co-director Rodolfo Sacchettini, an expert in the history of Italian radiodrama, was not just a special program for children, but also an opportunity to reflect on the ancient alliance between theatre and radio. Mass radio, since its relatively recent origins (the 1920s and 1930s), has always looked to theatre as a source for creating radiodramas and readings. At Santarcangelo 13, this relationship between the two worlds, this exploration of the childhood of radio, was reinforced by two Italian premieres, two radio conferences for children (broadcast live on Radio 3, but also performed live for the festival audience) that highlighted two important figures from both early radio experimentation and pedagogy.

Marco Cavalcoli, from the Fanny and Alexander company, read Walter Benjamin’s Radio Conferences. Between 1929 and 1932, Benjamin delivered real lectures aimed at children between the ages of ten and fifteen, which are still important today for understanding the radicality of his political and educational thought. Cavalcoli immersed himself in Benjamin’s words, telling stories ranging from Kaspar Hauser to Cagliostro. The figure of Janusz Korczak, still too little remembered, was the focus of Pedagogia scherzosa by Roberto Magnani of the Teatro delle Albe: a unique opportunity for a public reading of some texts, translated for the first time, by the great Polish pedagogue, created for radio in the 1930s in the form—now inconceivable—of an exclusive children’s program. Korczak’s figure (a student of Pestalozzi, the father of modern education, and promoter of new pedagogical techniques alongside Montessori) is tied to his experience at the Orphanage in the Warsaw Ghetto and his tragic death, along with his children, in the Treblinka concentration camp. Korczak’s words, interpreted by Magnani with the right energetic and assertive spirit, are scandalous, ironic, and contemporary: ranging from the hilarious catalogue of how to treat play wounds to stern warnings about becoming good citizens, and even to messages to adults, as the child is like a stranger whose ignorance must also be respected.

Radio and Childhood was not limited to these two important historical recoveries but also attempted to give voice to contemporary experimentation. Two projects sought to rethink theatre from the perspective of radio: Marmocchio by Sacchi di Sabbia, a kind of Pinocchio reimagined as a radiodrama set in a marble quarry, and Giallo by Fanny and Alexander, a live radiodrama created through a recording of a workshop with children led by Chiara Lagani. Public listening was central to the festival’s days, so much so that, in collaboration with the “Piccolaradio” project from Radio 3, which is spreading materials from the rich archives of RAI online, a listening room was set up, featuring an old radio where visitors could stop and listen to a selection of the most interesting children’s radiodramas from the origins of radio to today. The festival closed with an important public listening event, almost a ritual officiated by theatre anthropologist Piero Giacchè, who introduced a radio version of Pinocchio by Carmelo Bene, one of the rarest Beneian radiodramas, created with many actors in the 1970s.

The impression left by Santarcangelo 13 is that theatre and radio share a similar fate: a crisis in relation to competing media (consider the total pollution of images) and a crisis of ideas and vitality compared to other languages. If it is true that when we talk about the crisis of theatre, we are reckoning with the history of theatre, and this history reflects a radical transformation of society (call it the new global technocracy) made up of a new hypermediated and altered human/spectator (call it post-human), then one possible path of research and commitment today could be theatre for children. Theatre for the “little ones” immediately raises a political and pedagogical question because the next person to experience the performance is not a spectator, not a peer, nor an “user” belonging to the same community, but “the person who will come.”

Or, as Chiara Guida from Societas Raffaello Sanzio pointed out in a meeting at the festival, theatre has always been oriented in this direction, seeking the childhood of theatre, an authentic and self-critical question based on unfeigned experience. It is no coincidence that not only in theatre but also in the good and useful books and films of contemporary Italians and foreigners, the theme of childhood—and adolescence—is increasingly a common denominator, an urgent need. Artists and works seem to question the future, trying to answer the ultimate question, in a world now irreparably spoiled by commodities and profit, which philosopher Baudrillard posed before his death: “Why hasn’t everything disappeared yet?”

Perhaps this is humanity’s great work of art: the coexistence of the death and destruction instinct (of the environment, for example) and the imagination of a future, in every new life and new birth. The theatre saved by children is one that proposes a vertical vision, not flattened on the horizontality of relationships as much of new theatre in search of a new social commission does. That theatre, which in essence and truth, is nothing but a game. A theatre that can truly propose change and growth for everyone, not just for children.

Fanny & Alexander and Education: “We live in a childlike society…” by Luca Manservisi, Ravenna & Dintorni, Thursday, December 4, 2014

The show Giallo returns to Ravenna (from December 10 to 14 at Ardis Hall), a sort of chamber version of the Discorso Giallo by the Fanny & Alexander company. “Giallo” was the second stop in the Discorsi cycle (after the gray one, on the theme of political rhetoric), and it tackles the thorny issue of education. The only performer is Chiara Lagani, who in Giallo applies the outcomes of extensive workshops conducted with elementary school children from Parma and Ravenna. We interviewed her.

Why tackle the theme of education?

“Education is one of the seven human realms that our discourses touch upon, but it is also one of the first we wanted to address, right after politics. Perhaps because it is closely linked, together with politics, to the idea and life of a society. Not by chance, every time you reflect deeply on school, or better, on school life, the image of a very well-defined microstructure of society immediately comes to mind. It’s as if moving from the idea of education and formation is also necessary to understand the political nature of the life of our society. To better understand what education meant, I felt the need to meet children directly.”

Which children? And how?

“Luigi (De Angelis, founder and author of Fanny & Alexander with Lagani) and I identified five or six types of workshops for children aged five to ten. I chose this age because, working also on the theme of the toxicity of the real, of the contemporary, I thought this was the time when the seed of toxicity first settles in the child, when they lose some of their innocence. In some cases, you are facing little adults. But the boundary is clear: some children are just before that boundary, others have already crossed it, and the last ones are teetering on the line.”

How did the work develop and how many children were involved?

“Each module was a theatrical game designed for them, and it differently explored the theme of education. We involved six or seven classes, plus a group of about twenty children whose parents brought them in the afternoon to our headquarters, Ardis Hall. Offering a game was a way to ask them a very serious question about education.”

What were the biggest difficulties? And the satisfactions? What did the children teach you?

“Something truly unexpected happened. I felt astonishment, fear, love, awe, admiration, discomfort, and more, in relation to them. The strongest thing was realizing that in direct confrontation with their experience, their instinct, it is very difficult to have an image of ourselves that matches their behavior. Every gesture, every word, many of the responses they gave, certain tones I heard in my own voice, inevitably fell, even partially, into a cliché. The mother, the hen, the teacher, the animator. It’s difficult to remain pure in the face of a group of children, their questions, their direct way of speaking, and even their repeated, minuscule, monstrous mimicking of adult behaviors, like those of their parents.”

How do you get out of this?

“The only solution I found was to assume the role of a character, which I embraced by making a very precise and tight contract with them, through which we could together plunge into the realm of the game. And so, a strange, almost involuntary dramaturgical process occurred: all the readings I had done, the words of the great classics of pedagogy, turned into bricks, pieces that built and nourished the different narratives I proposed to the children, not to entertain them, but to find out from them, in the end, the mysterious meaning behind education, what it means to educate, what it means to be educated. Through theater, we managed to discuss all this.”

What message do you want the show to convey, particularly to those with children?

“The show is truly an appeal to our childlike part. There is always this part that breathes within us, and sometimes we forget about it. The starting idea was to work on the discrepancy between the adult and child parts within each of us. It’s as if in every one of us there’s a child who never fully managed to be a child, like some of the children I meet, who in some cases seem like premature adults in a society that often removes childhood, does not allow it a natural space, and thus does not understand or welcome its needs, providing models that are already irreparably adult. Constantly in the discourses of the children I encountered, there are adult models, almost every sentence they utter hides an adult speaking through them. There’s something paradoxical in this because there are also adults incapable of being adults. Our society is childlike, unable to grow, but at the same time, it has removed childhood as a true possibility: so, children cannot be children, and adults are not yet adults. I believe that looking at childhood with attention, respect, and love helps us reconcile with a part of ourselves: a parent, through their child, does not perhaps see the world for the second time? Doesn’t he perhaps relearn the names, the things, the colors once again through them? This is a huge opportunity, isn’t it?”

What are the next projects for Fanny & Alexander?

“We are working on Discorso Verde, featuring Marco Cavalcoli. It will be a work on prodigality and greed, on the relationship with money and its absence, from the economic miracle to the global crisis. We will debut this summer with two performances leading up to the Discorso (which will debut in the fall), the first Scrooge, based on Uncle Scrooge McDuck’s lesson on money to his nephews, the second Kriminal Tango, a tribute to Fred Buscaglione. And then we have a Magic Flute in the works for which we are handling the direction, dramaturgy, costumes, and staging, commissioned by the Teatro Comunale of Bologna. It will be a 3D opera, working with video-makers Zapruder, and will debut on May 16.”

Giallo, a Live Radio Drama, by Annamaria Corrado, Il Resto del Carlino, Tuesday, December 9, 2014

Giallo, a live radio drama, can be considered a chamber version that is completely autonomous from Discorso Giallo. “Giallo” is a mysterious and ghostly radio dialogue between a shifting teacher figure and her invisible class. This creation also fits into the path Fanny & Alexander has followed in recent years. As part of their research into various forms of public oratory, the “yellow” (giallo) is the second phase of the cycle (after the gray one, on political rhetoric, interpreted by Marco Cavalcoli) and addresses the thorny issue of education. The only performer is Chiara Lagani, who in Giallo puts to use the results of long workshops conducted with elementary school children from Parma and Ravenna. The children’s voices, which provide the soundtrack to this radio drama, are actually recordings taken from the workshops.

In the show, Chiara Lagani plays the quintessential teacher with whom one confronts as a child, a figure who is both bitter and feared, questioned, here seen in a curious “game of opposites”, where even without physically appearing, it is the children who are the true protagonists, dictating the rules and establishing the point of view. Particularly suited to unconventional spaces, the performance unfolds around a large platform, with the audience gathered on three sides. On the fourth side, the performer moves, engaging with the spectators who, at the start of the performance, like at school, are called to respond to the roll call in person.

Giallo – Short Theatre 2013, MACRO Testaccio La Pelanda (Rome), by Rosy Brenca, saltinaria.it, September 16, 2016

Fanny & Alexander arrive at Short Theatre 8 with a live radio drama. The show is a clear attack on politics, any form of racism, subcultures, and especially on the current educational institution, which has lost its fundamental role, namely educating for diversity and teaching not to fear others. This is all seen from the perspective of elementary school children. The children’s figure takes on a dual role: in addition to showing the world through their perspective, it also gradually helps the spectators rediscover the child still present in each of them, who asks new questions and, consequently, demands new answers and solutions.

The show begins in the dark. The audience – and their patience – is put to the test. The darkness of the room lasts for several minutes, intensified by recorded voices coming from various corners of the room. Suddenly, a faint light comes on, illuminating a table with a black model on it: a school, and the recorded voices surrounding the viewer are those of children. The phrases they speak are always the same, creating a sense of disorientation, confusion, and anxiety – though a pleasant one – since the phrases are sweet and innocent.

After a few minutes, the only character of the drama enters: a teacher, dressed like a German governess from times past. She takes attendance, introduces herself, and begins to interact with the class. She tells the children a story about a strange creature – which we will later learn is a black gorilla – and the difficulty she faces communicating with it. To solve the problem, she asks the children for help, who at first are quite scared of the creature: they run away, scream, some cry, and they are all very distrustful. Gradually, the children’s reactions change as the teacher encourages them to interact with the creature and teach him to speak. Ultimately, the creature learns how to say “please” and “thank you”, and, as the teacher encourages the class to be kind, it goes from “terrible” to “beautiful”. At that point, we realize that the creature represents racism.

A story of prejudice, racism, and lack of education, transformed by the children’s imagination and their peculiar game. This teaches the viewer to be able to relate to something unfamiliar, to make a real effort to listen to it, to understand its value. From this point of view, Giallo becomes a very powerful weapon in favor of diversity.