Se Questo è Levi

Itinerant Performance/Reading on the Works of Primo Levi - Special Ubu Award 2019 Ubu Award 2019 - Best Actor or Performer under 35 to Andrea Argentieri

- With Andrea Argentieri

- Directed by Luigi De Angelis

- Dramaturgy by Chiara Lagani

- Organization by Maria Donnoli, Marco Molduzzi

- Communication and Promotion by Maria Donnoli

- Produced by E/Fanny&Alexander

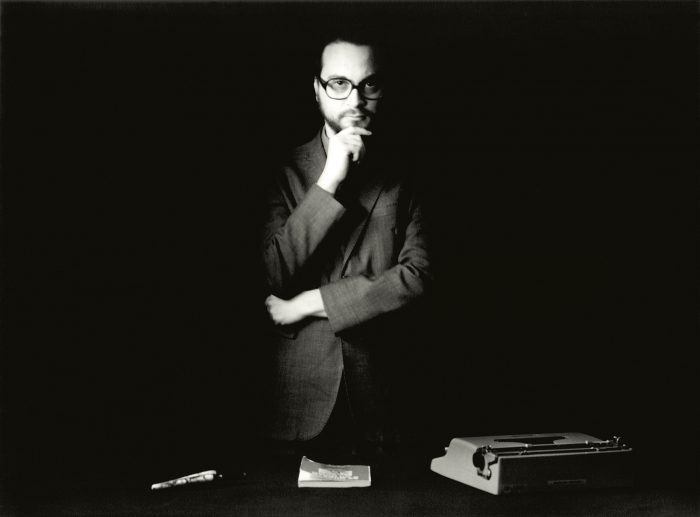

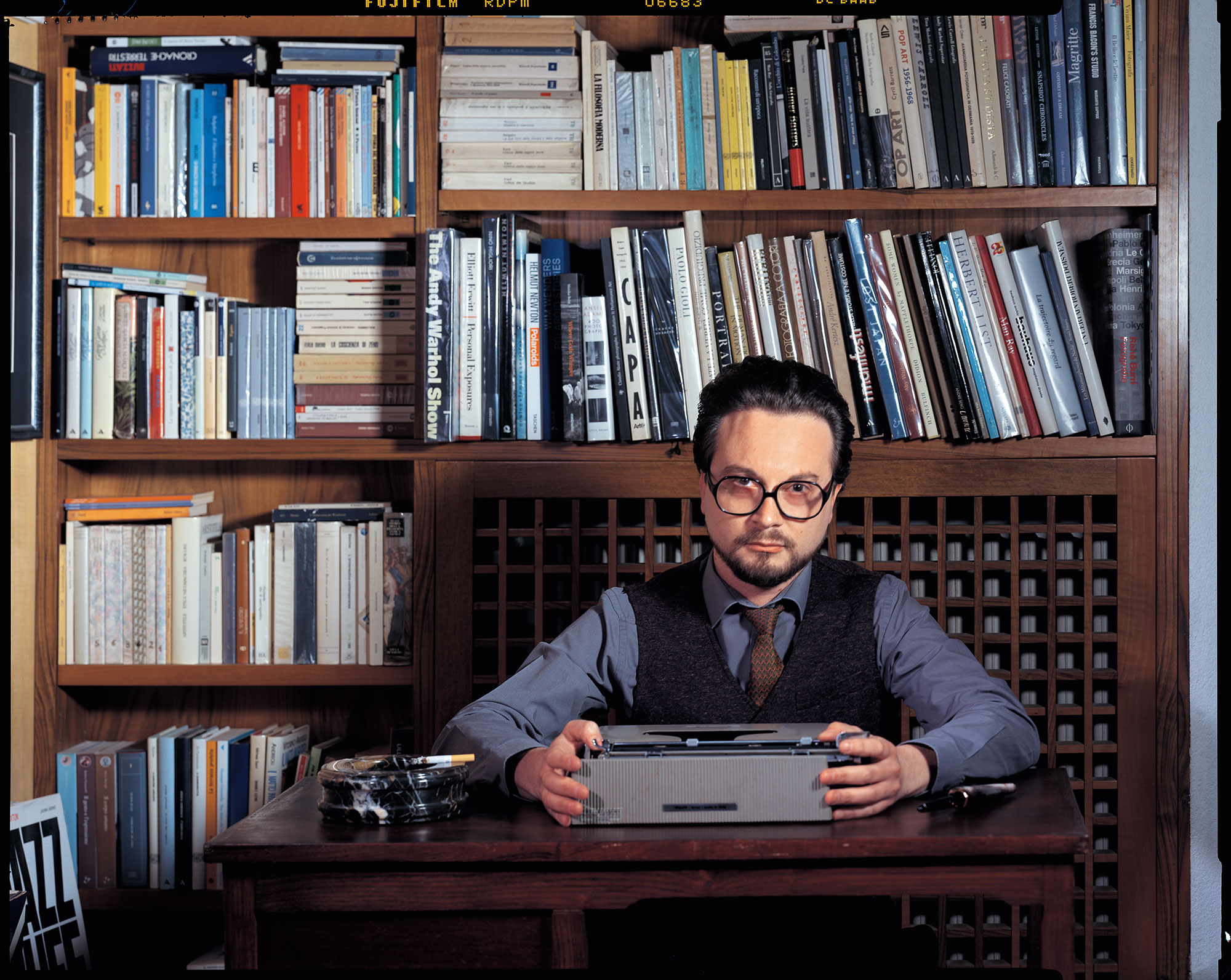

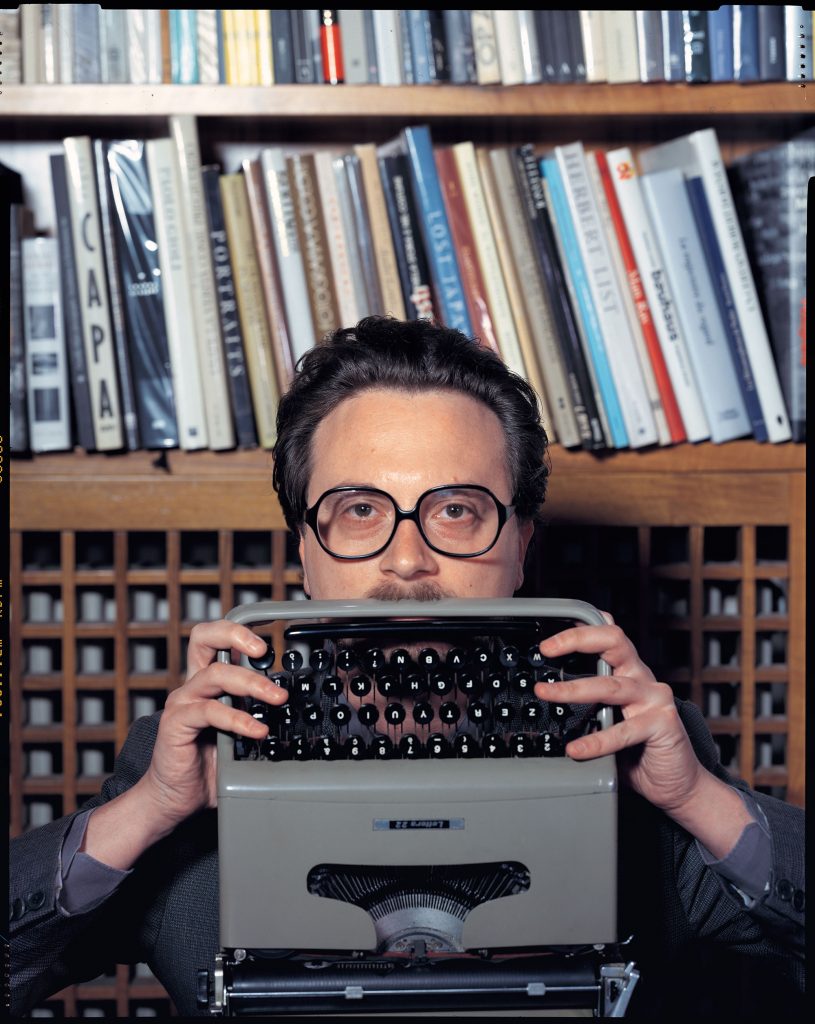

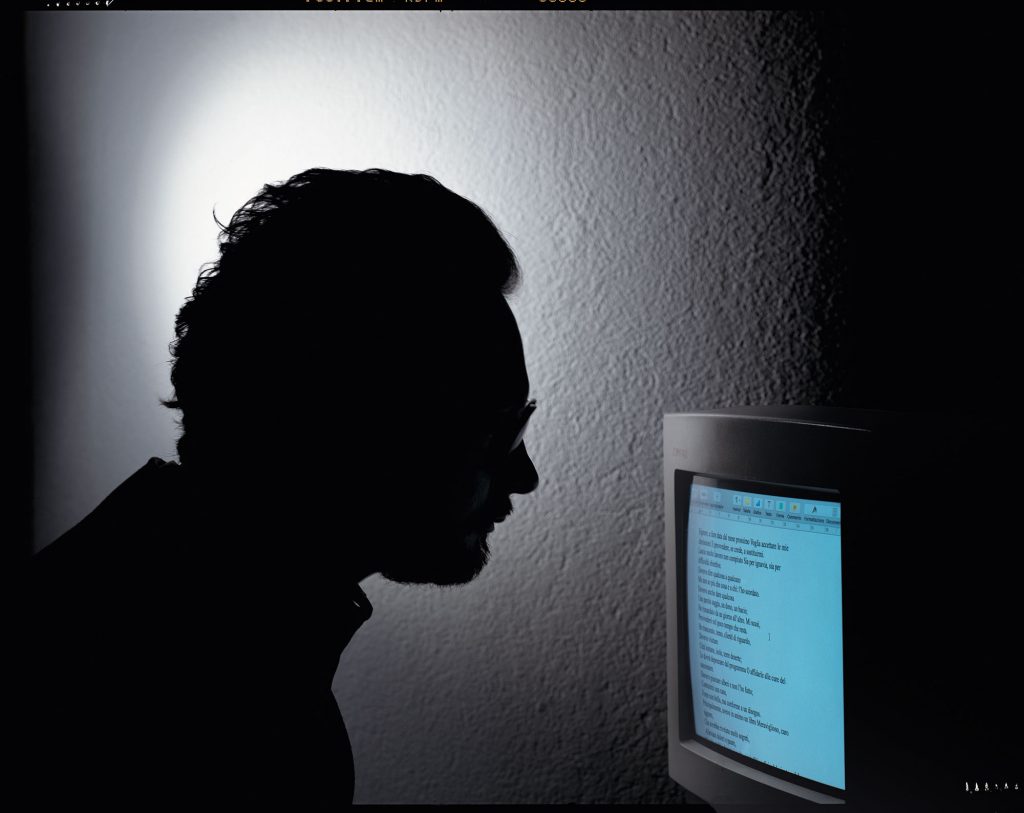

Based on audio and video documents from the Rai archives, Andrea Argentieri takes on the role of writer Primo Levi, adopting his voice, gestures, postures, tones, and first-person speeches. It is an intimate encounter, where the writer, grounded in the truth that inspired his works, testifies to his experience in the concentration camps with a lucid testimony technique, distilling memory with the clarity of a gaze capable of expressing the unspeakable from the seemingly serene perimeter of reason.

Year : 2018

Three symbolic locations have been identified where the writer can be encountered: a private study, a lecture hall, and the room of a municipal council. Each of these three places poses a different question in relation to three of Levi’s works: If This Is a Man, The Periodic Table, The Drowned and the Saved. The most intimate relationship between Levi and his writing, the vital necessity of testimony, his relationship with his father and family, his belonging to Jewish culture; the lifelong relationship between chemistry and writing, the dignity of labor, and the communal function of literature; the public need for a narrative that possesses the scientific transparency of a chemical process; the theme of judgment, the inquiry into the necessity of suspending hatred in favor of an analytical entomological curiosity.

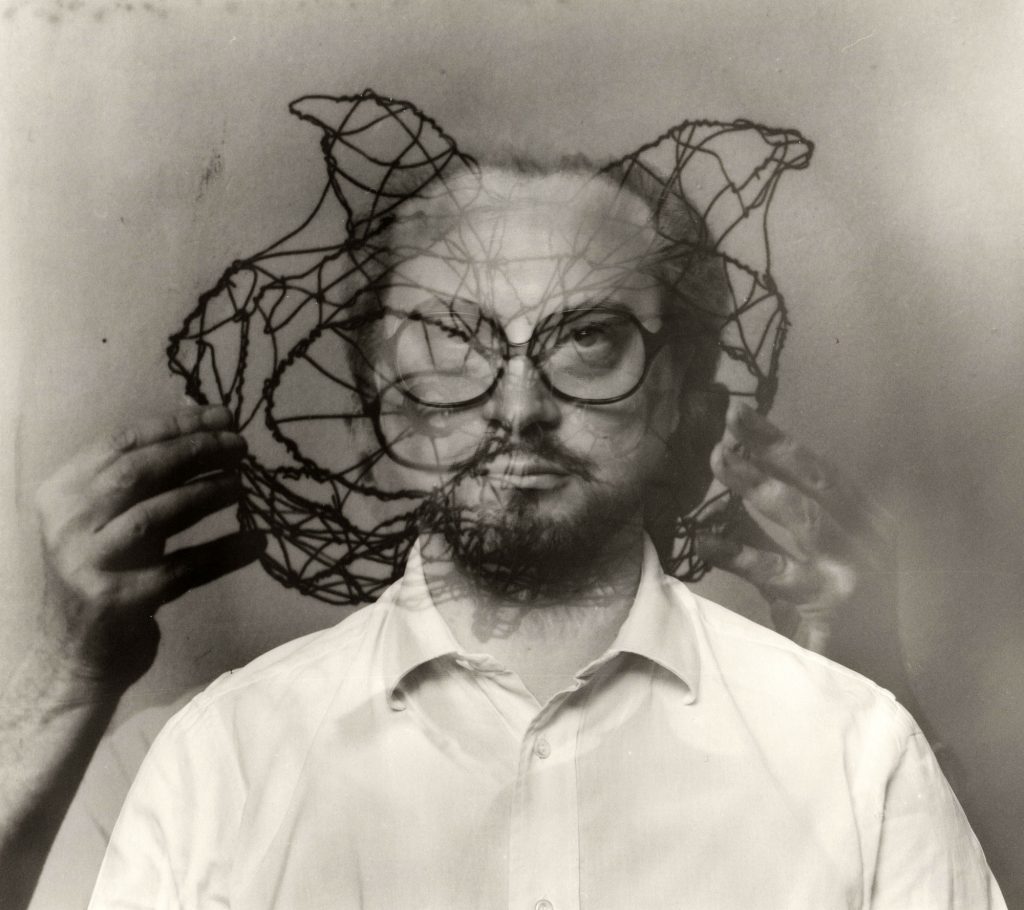

Through the technique of remote acting and hetero-direction, Andrea Argentieri creates a portrait of the writer that is based on the vertigo of a question: how much is this testimony still biting and capable of speaking to us through the sensitivity of an actor who allows himself to be permeated by the original materials left to us by that writer? Can the epiphany of a voice, of a body-soul, imprinted in the body of an actor much younger than the model-imprint he pursues, evoke even more compellingly the power and necessity of its testimony?

If This Is Levi is an actor’s portrait. It is the attempt to materialize the experience of recounting, face to face with the writer.

The Obsession with Super Realism

In his book The Drowned and the Saved, Primo Levi speaks of an almost obsessive attempt at super-realism in the German translation of If This Is a Man, wanting the translation to be a kind of direct tape recorder of experience, a sort of back-vision of the language or a posteriori restoration… This obsession was the driving force behind the project If This Is Levi and its guiding principle. To put an interpreter, an actor, in the position of being permeated by the recorded voice of another life, to wear that voice like a skin, to take a spiritual bath in it, to soak it up, like a ball of wool soaking up water. Inside the voice of a writer with as multifaceted a personality as Primo Levi’s lies a rich world, full of emotions, held back or released. In it, one can glimpse a complex watermark; hidden in the grain of the voice are the traumas of experience, but most of all, the full force of character, reason, and mission. In If This Is Levi, the performer does not read, but is “read” by a foreign voice that passes through them, making them react to – as in a chemical process – the sound material that is delivered to them via an earpiece, which they immediately reproduce, having studied the writer’s proxemics, facial expressions, and both their inner and outward emotions, having allowed that other life, that other spiritual skin, to dwell in them through a sonic bath. It is a form of mimicry by proximity, where one must know how to make space, welcome, seek out the inner similarities, the correspondences with one’s own experiences, respect, reverberate; it is a form of meditative observation, where one must not give in to volitional or affirming temptations but rather know how to capture, become an antenna, intercept, be permeated, and let it flow. As Marco Belpoliti points out in Primo Levi, Front and Profile, in Levi’s writing, the force of orality can be felt, as if Levi were primarily an oral writer rather than a pen writer. One can hear in his writing his need for testimony, as if his texts had been “tested” first in train journeys, at home, in conferences, in front of various audiences he encountered and never avoided… Conversely, his radio or television interviews are incredibly lucid, as if they were written the moment they were uttered, showing a continuity between orality and writing in both directions. For this reason, we chose not to stage Primo Levi’s literary works, apart from a few excerpts from The Periodic Table, but rather to linger in the overwhelming power of his oral language, from which vivid concepts emerge that seem to be spoken for the first time in the instant they are uttered by the interpreter, making them seem like words of today, sharp arrows, political responses to the grey area of these times.

Luigi De Angelis

TOUR

- 28 January 2018 | Bologna, La Via Zamboni for the 2018 Day of Remembrance

- 10-13 October 2018 | Ravenna, Fèsta018

- 9-10 March 2019 | Carpi (MO), Vie Festival

- 29 June 2019 | San Gimignano (SI), Nottilucenti

- 30/31 July 2019 | Rimini, Le Città Visibili

- 9/10/11 August 2019 | Albenga (SV), Terreni Creativi Festival

- 6/7 September 2019 | Mantua, Festival della Letteratura

- 20 October 2019 | Massafra (TA), Teatro delle Forche

- 22-24 November 2019 | Rome, Teatro Argentina

- 17 December 2019 | Zurich, Politecnico Federale

- 23 January 2020 | Casalecchio di Reno (BO), Teatro Comunale Laura Betti (matinee)

- 24 January 2020 | Modena, Istituto Storico della Resistenza

- 26 January 2020 | Reggio Emilia, Sala degli Specchi del Teatro Valli

- 27 January 2020 | Bologna, Aula del Consiglio Comunale

- 19/27 January 2020 | Bologna, Museo Ebraico (AD ORA INCERTA)

- 1 February 2020 | Valdagno (VI), Biblioteca e Aula del Consiglio Comunale

- 7-9 February 2020 | Cremona, Teatro A. Ponchielli

- 16/23 February 2020 | Bentivoglio (BO), Castello – Istituto Ramazzini

- 1 July 2021 | Naples, Emeroteca Tucci – Palazzo delle Poste Centrali

- 2 September 2021 | Forlì, Festival Crisalide – Teatro Felix Guattari

- 14 September 2021 | Pistoia, Teatri di Confine – Villa Stonorov

- 14 October 2021 | Faenza, MEME Festival, Sala del Consiglio del Comune

- 18-20 February 2022 | Rome, Angelo MAI

- 23 April 2022 | Castel Maggiore (BO), Agorà, Teatro Biagi D’Antona

- 7-8 May 2022 | Brussels, Kunsten Festival Des Arts – Belgian Senate

- 1 October 2022 | Belluno, Vertigini, Teatro Comunale

- 2 December 2022 | Pavullo (MO), Teatro Mac Mazzieri

- 5 December 2022 | Fidenza (PR), Teatro Magnani

- 6 December 2022 | Scandiano (RE), Teatro Boiardo

- 7 December 2022 | Morciano di Romagna (RN), Auditorium della Fiera

- 24 January 2023 | London (UK), Italian Cultural Institute

- 27 and 28 January 2023 | Ravenna, Sala del Consiglio Comunale

- 30 January 2023 | Venice, Asteroide Amor @ M9 Museo del ‘900

- 31 January 2023 | Venice, Asteroide Amor @ Teatro Goldoni

- 3 February 2023 | Bucharest (Romania), Teatro Ebraico in collaboration with the Italian Cultural Institute

- 5 February 2023 | Cluj-Napoca (Romania), Tranzit House in collaboration with the Italian Cultural Institute

- 22-24 June 2023 | Shanghai (CN), Great Theatre of China in collaboration with the Italian Cultural Institute

- 25 January 2024 | Tirana (AL), Teatro Metropol in collaboration with the Italian Cultural Institute

- 27 January 2024 | Vicenza, Sala del Consiglio Comunale

- 6-7 March 2024 | Milan, Palazzo Marino

- 27 January 2025 | Cascina, La Città del Teatro

- 29 January 2025 | Pergine, Teatro Comunale

[ph. Koen Broos]

••••••

Mimetismo per vicinanza, by Ludovico Cantisani | Persinsala, February 20, 2022

The Fanny & Alexander company reinterprets the person – even before the work – of Primo Levi through a theatrical journey of particular depth and reflection. On stage at Angelo Mai.

Winner of two UBU awards in 2019 – for Best Performer Under 35 for Andrea Argentieri and an UBU Special Award for the project suitable for the entire company – Se questo è Levi by Fanny & Alexander returns to Rome. In the production staged at Angelo Mai, Argentieri portrays the writer and chemist from Piedmont at the center of an audience arranged on all four sides of the actor. The audience is given a list of around thirty questions to ask Levi in any order; the answers are all based on statements actually made by Levi in numerous public encounters and interviews, many of which are now preserved in the Rai archives, either on television or radio.

This exploration of Primo Levi’s public testimonies, beyond Se questo è un uomo which marked its beginning, on one hand highlights the semantic ambiguity that runs between witness and martyr, and on the other represents for Fanny & Alexander the occasion for an ambitious yet minimalist reflection on the status of the actor.”In Se questo è Levi, the performer does not read, but is ‘read’ by a foreign voice that passes through him, reacting to the sound material presented to him through an earpiece, which he instantly responds to, having studied the writer’s proxemics, facial expressions, and his inner and outer emotions,” reads the director’s notes, signed by Luigi De Angelis. “A form of mimicry by proximity,” is the conclusion. By openly applying the formulas of remote acting and hetero-direction, Argentieri pushes the practice of acting mimesis to a radical, almost sinister threshold, blending testimony and performance in a paradoxical but not illusory resurrection of Levi.

Fanny & Alexander have always conducted interesting experiments in the theatrical adaptation of works that are not traditionally theatrical: among their most recent efforts, the show Sylvie & Bruno, presented shortly after the release of the new Einaudi translation of Lewis Carroll’s novel of the same name by Chiara Lagani, a co-founder of Fanny & Alexander and the dramaturge of Se questo è Levi. As Levi himself stated in one of his answers included in the show, and as Marco Belpoliti notes in Primo Levi di fronte e di profilo, Levi’s writing possessed an intrinsic orality, and the writing of Se questo è un uomo had gradually overlapped with similar oral testimonies from the survivor, starting from the first weeks after his return to Turin, following the long journey narrated in La tregua.

A kind of symmetrical operation to the one attempted by Fanny & Alexander in Se questo è Levi – through the acting of Andrea Argentieri – can be found in the chapter Lettera ai tedeschi (Letter to the Germans) from I sommersi e i salvati (The Drowned and the Saved), placed, not coincidentally, at the end of the performance. In Lettera ai tedeschi, Levi recalled the history of the German translation of Se questo è un uomo, and the special relationship that developed with the translator. Reflecting retrospectively on that translation, thanks to the correspondence exchanged with the translator, Levi admitted to a claim of “super-realism” in the rendering of the text, which was all the more crucial in the German edition, since it was in that language that most of the orders and commands Levi heard at Auschwitz were spoken. Recalling also the positive reviews that specifically praised the style of the German edition of Se questo è un uomo, Levi acknowledged the translator’s fundamental and notable fidelity, despite the many lexical compromises the translator had persuaded him to make in order to adapt the camp jargon to the German spoken at the time.

Since these words close the show, it is clear that Fanny & Alexander hope to have demonstrated the same fidelity and mutual super-realism in translating Levi’s person onto the stage. As we can judge, with Argentieri even imitating Levi’s lapses during speeches, this fidelity exists and takes mimesis to its extreme. Behind the show and its simplicity lies a considerable theoretical effort, with numerous implications induced by the status of the organic simulacrum in which Argentieri is placed. But recovering, with the artwork in the age of technical reproducibility, the paradoxical challenge of a physical, organic, bodily reproducibility of the actor – is no small feat. It is, moreover, the opposite of that identification with the character so heavily promoted by the Actors’ Studio and similar methods: identification is aimed at characters, whereas imitation, at least in this form, is directed at a person who had a historical experience and imposed a very specific social function. Thus, Se questo è Levi brings to us the echo of Levi’s testimony: in a form far stronger and denser than any archival recording.

••••••

Ieri come oggi e come domani?, by Caris Ienco | Persinsala, October 17, 2020

What would happen if, after many years, a historical personality returned among us and we could ask them questions? This is not exactly what happens, but something very similar in Se questo è Levi, by Fanny & Alexander – a multi-award-winning show in 2019, presented as part of the Materia Prima festival at the Chiostro Grande of Santa Maria Novella.

Seated in two rows, like at a Pitti Uomo fashion show, we wait expectantly for the performer to appear in front of us. In the meantime, we consult a list of questions. A voice instructs us on the behavior expected from the audience, and shortly after, the actor, Andrea Argentieri, enters. He looks like Primo Levi, the Piedmontese chemist/writer and Auschwitz survivor.

The show begins, the performance begins!

The performance starts with a re-enactment of an interview with Primo Levi, taken from some Rai archive footage – some of which can easily be found on YouTube. On stage, however, the interviewer is missing because we, the audience, must play that role. The audience will dictate the order and rhythm of the scene. There is a written script, but it is fragmented and can be recomposed depending on the sensitivity of the present audience – and through this theatrical game, the famous interview is reworked.

Throughout the performance, the deportation of Levi is discussed, as well as human cruelty, but also the work of a chemist. The historical figure is present, entirely for us. The performer ‘becomes’ the interviewee through remote acting, hetero-directional – as described by the members of Fanny & Alexander. In simple terms, the actor is ‘possessed’ by an audio that suggests the correct answers – the real and authentic ones. Argentieri no longer exists; he is Primo Levi, literally, in every word and attitude. There is no free interpretation, nor a didactic one, but rather a reproduction of the model of the Piedmontese writer. The goal is to remain faithful to the idea that Primo Levi wanted to convey in Sommersi e Salvati, namely that of super-realism. The aim is to leave no detail of his reality out. The only freedom that can be allowed is the order of the questions and the rhythm.

Some spectators try to step out of line – either to provoke, out of curiosity, or because they have not understood the ‘rules of the game’ and risk asking off-script questions, to which the actor, rightfully, cannot and should not respond, as that would be a betrayal. The answers are authentic and never free. This attracts and entertains the audience, in addition to moving them. Indeed, it is hard not to be moved by such a strong yet fragile personality, who, despite the doubts surrounding the circumstances of his death, still possesses a vitality, energy, and strength to go on without ever leaving anything behind. The performance touches on historical topics but also very contemporary ones. It would be interesting to see the differences or similarities between different performances. What is discussed is not only curiosity or facts from a past that is still painfully sharp, but reflections on humanity that strike – yesterday as today. Themes of captivity are discussed, but there are also explorations of writing in its deepest sense, the will to live, but also to not disconnect from the past, the duty of memory but, at the same time, the concept of memory: a memory seen as a duty but one that must be carefully considered, as it is degradable, fallible, and, on the other hand, a memory that is too often evoked risks becoming crystallized. The generational contrast stands out: between the younger generation, forced into certain restrictions by COVID-19, but perhaps freer from material and economic constructs, and a world where poverty was feared, but not enough to stop unions or the desire to stay together. Also noticeable is the presence of the youngest generation, the children. The audience member who asked the most questions is from this age group.

••••••

••••••

Primo Levi recalled at Santarcangelo Festival, by Francesco Pace | Il Corriere dello Spettacolo, July 18, 2020

At the Santarcangelo Festival, the Ravenna-based company Fanny & Alexander returns: or rather – as they define themselves – the “art workshop” Fanny & Alexander. Indeed, their shows are “created” and “produced” for the theater in the same way a noble artisan would craft his creations or how the workshop artists made their works of art. The play I sommersi e i salvati is the result of one of these creations, the third in fact, of a trilogy dedicated to Primo Levi (entitled Se questo è Levi). Levi, the writer and chemist, was interned in the Auschwitz concentration camp. The title refers to the final work by the Turin author from 1986, in which he addresses the theme of memory, “a wonderful tool, but flawed.”

The council hall of Santarcangelo di Romagna provides the backdrop for this fascinating narrative/dialogue that Primo Levi (played by the excellent Andrea Argentieri, already the winner of the 2019 Ubu Prize) holds before the audience: his life, his relationship with his family, his Jewish faith; a complete unveiling once again, more than 70 years after the horrors. The audience is an integral part of the performance, the driving force of the action. Each person can ask Primo Levi a question (chosen from a list distributed before the performance), and he responds and discusses his views.

The dramaturgy – and thus Levi’s answers – are by Chiara Lagani, who draws inspiration from the audio and video documents in the Rai archives and from various speeches Levi gave to students during his many visits to schools. In fact, through the technique of heterodirection and remote acting, Andrea Argentieri takes on the posture, voice, and gestures of Primo Levi to such an extent that the words, movements, and stories seem like a free flow of the actor’s/Levi’s thoughts.

The direction, signed by Luigi De Angelis, superbly and successfully sought to evoke the spirit of Levi, attempting to answer the question, “Can the epiphany of a voice, of a body-soul, imprinted on the body of an actor much younger than the model-impetus he follows, still bring forth the power and necessity of his testimony?” In this sense, the director focused on placing Levi’s story in a sort of non-place so that his story could be as authentic as possible, stripping it of any logic tied to “traditional theater” (i.e., sets, special costumes). Another commendation goes to Andrea Argentieri, who naturally took on Levi’s words and gestures, confronting the unpredictability of the action and the audience.

It’s never easy to bring these themes and the stories of such personalities to the stage. I sommersi e i salvati succeeds in making these distant topics more relevant by placing the audience at the center, allowing them – now more than ever – to feel part of the scene.

••••••

Se questo è Levi, by Nicola Arrigoni | Sipario.it, February 12, 2020

“Primo Levi, in his book I sommersi e i salvati, speaks about the almost obsessive attempt to overcome realism in the German translation of Se questo è un uomo, wanting the translation to be a kind of direct tape recorder of the experience, a kind of back-vision to the language or retrospective restoration.” This obsession became the driving force behind the project Se questo è Levi and its guiding principle,” writes Luigi De Angelis in the director’s notes for Se questo è Levi, a three-part journey dedicated to the author of Se questo è un uomo. The director retrieved audio and video materials from the Rai archives and YouTube: interviews with the writer, and created a sound dramaturgy, entrusting these materials to the sensitivity of Andrea Argentieri, an actor under 35 who won the Ubu Prize. Argentieri embodied the voice and words of the writer through the technique of remote acting and heterodirection. This is a stylistic and research hallmark of Fanny & Alexander – as seen in their staging of L’amica geniale – but here it goes further. With Levi, the process is taken a step further, projecting towards an ethical and aesthetic mimetism where the distance of the actor and the proximity to the material being interpreted create a symptomatic short circuit with the space. The key term is the ‘super-realism’ borrowed from Levi, which challenges De Angelis. In his journey into Primo Levi’s thought, the director of Fanny & Alexander seeks three places: a study where he reconstructs the intimate and private writing space of Levi for the first part, Se questo è un uomo; a scientific classroom where the lesson from Il sistema periodico unfolds; and a public space: a square or a town council chamber, where a collective interview with the author of I sommersi e i salvati takes place. The experience can be done on different evenings or in a single occasion for a total immersion in what is characterized as a meeting.

When discussing the Se questo è Levi operation, it seems appropriate to state the “where” and “when.” Paradoxically and emblematically, Se questo è Levi was seen in different spaces within the Teatro Ponchielli in Cremona. Is this a betrayal of the original? Perhaps. Certainly, the theater is, in its own way, a public space, a place that represents the community. Se questo è Levi thus found itself in the non-designated spaces of the theater: the foyer, the large stage of Ponchielli transformed into a scientific classroom and assembly space, serving as the metaphor for those hyper-realistic places sought by De Angelis. In the Cremona performance, these spaces appeared as absolute, making Argentieri’s performance an inquiry of the collective across time and history. But to achieve this, it was initially necessary to create the encounter, to resurrect the Turin writer, embodied by a strikingly similar Andrea Argentieri, who mimics Levi but does not imitate him.

Se questo è un uomo – In Se questo è un uomo, the audience – fifty spectators at a time – settles into the pink room of the Ridotto at Ponchielli. A desk, a typewriter, some pens, and a bookshelf. This is Primo Levi’s study. What happens is an encounter with Levi, his thoughts, reflections on death, his experience in the camps, and his role as an intellectual. Andrea Argentieri – who hears Levi’s voice through almost invisible earphones – does not imitate but is him, does not pretend but lives Levi’s thoughts and voice. With him, there is a sense of having a real encounter with the writer, interviewed a year and a half before his suicide at his family home in Turin, April 11, 1987. Argentieri seems almost in a trance, speaking and moving with mathematical, systemic precision, in perfect adherence to the scientific and technical systematicity that Levi used in his testimony as both intellectual and survivor of the camps. There is not a single misplaced tone, nor any slip-up in his gestures or voice. Yet, for the audience present, there is no pretense, no interpretative distance: we are in the presence of Levi, and we forget – especially due to the proximity and resemblance – that the writer is dead. The author of I sommersi e i salvati is magically there among us, talking with us, and we find ourselves listening to him, almost in a trance ourselves. Fiction and reality become one because what Andrea Argentieri does is embody Levi’s words, or rather his voice, giving form to his thoughts with a monstrous effectiveness that leaves the audience speechless.

Il sistema periodico – For the second part of Se questo è Levi: Il sistema periodico, the Ponchielli stage is transformed into a chemistry lab. Large tables, the inscription “Arbeit macht frei” (work sets you free) on the fire curtain, some chemical formulas, and the periodic table. A chalkboard and a workbench with flasks and test tubes complete the setting. This is the context for the second leg of the journey in Se questo è Levi: Il sistema periodico. Andrea Argentieri wears a white lab coat and moves between the benches, seeking contact with the audience, addressing the spectators. Levi, the chemist, and Levi, the writer: Levi, who made chemistry his profession, and Levi, who viewed writing as a non-job, done in the night or during vacations, but no less demanding. Argentieri surprises again with his acting intensity, speaking in a round, warm, controlled, yet natural tone – naturally artificial, one might say. What comes from the director’s console of Luigi De Angelis through Argentieri’s earphones is transmitted to the audience with a vocal warmth that cools when Levi engages in reading excerpts from Il sistema periodico. Levi’s testimony as a writer in the Rai interviews and written pages intertwine to create a reflection linking chemistry and writing. Sublimating, refining, distilling – all chemical processes – become metaphors for thought that Argentieri offers to the spectators, who are called into the action, questioned by an actor who seems moved by an external force. Unlike the first part, in the writer’s study (i.e., the Ridotto’s Sala Rosa), where proximity was physical, the vastness of the stage changes the dynamics, offering a more official version of Levi – not lecturing, but undoubtedly playing the distance of the scientist who investigates, studies, and rationalizes. Yet, reason fails when it comes to describing the camps, explaining why that inscription sounded ironic, or how work did not set anyone free, but rather saved them. Perhaps.

I sommersi e salvati – “Do you think it is possible to annul the humanity of a man?” is one of the questions on the questionnaire that spectators received to interrogate/interview Primo Levi in the final part of Se questo è Levi. The audience, arranged on three sides of a square, asked questions to Levi/Andrea Argentieri, in a collective interview with the author of I sommersi e i salvati. The first question was posed by a child, an instinctive – though not random – choice. The young interviewer chose one of the questions – the last on the list – detached from the chronological horror of the camp experience and focused instead on the universal aspect of inhumanity. This is the true value of the Se questo è Levi experience. In Levi’s responses – selected by Luigi De Angelis and sent through the earphones to Andrea Argentieri – there is, beyond the recounting of the deportee’s experience, a present urgency when talking about the crystallization of memory, writing as testimony, or the imminent danger that the camp experience may resurface. Immediately, one thinks of Libyan detention camps, the migrant trade… and yet what Levi says is from thirty years ago. This is also the strength of this mimetic Levi, pressed by the questions of the audience, who plays along in building a questioning dialogue that unites us in a historical reflection destined to incarnate itself in the present, and perhaps even in the actor’s body. How much would Mario Apollonio have liked this work – in all its didactic nature – and his Storia dottrina e prassi del coro? Thanks to Fanny & Alexander, Primo Levi has returned to be close to us, becoming the body both interrogated and questioning. The words of the author of I sommersi e i salvati, prompted by the audience’s questions – like the tracks of a testimony playlist – have taken on a surprisingly timely meaning. Hence the choice of the child to ask that first question (the last on the list), free from history and projected into the universal that questions the particular. Se questo è Levi by De Angelis and Argentieri gives the rare ability to subliminate reality into hyperrealism, which, in its obsessive precision of rendering the original, becomes symbolic – a sign that encompasses everything and interrogates us, aided by the technique. Techné, in Greek, means art. Luigi De Angelis, through the technique – the audio recordings, the transmission of the voice to Argentieri, and his bodily translation in managing vocality – has created a kind of resurrection of Levi’s thought, an incarnation of his words and voice, marked by a mimetic realism that ultimately triumphs in an abstraction that questions all of us, beyond time and history, and perhaps even beyond good and evil.

••••••

In the Body of Primo Levi, by Daniela Garutti | Istituto Storico Modena, January 27, 2020

More than facing an actor playing the role of Primo Levi, in Se questo è Levi one feels as though they are in the presence of a body— that of the talented Andrea Argentieri— filled and animated by the words, gestures, and even the Turin accent of the man, Levi.

In a metaphorical and real journey from the inside to the outside, from the intimacy of a study to the full exposure of a council chamber, that of the Municipality of Modena, the audience witnesses the autobiography of the writer, unfolding through answers to off-stage questions, readings of Levi’s works, narrative, and, lastly, questions from the audience.

The experience of the camp, the need-duty of testimony, his work as a chemist and a writer, the study and language, religion, the reflection on the past and present— Levi’s entire thought and life unfold in three stages: a study set up in the Crespellani Hall of the Civic Museums, where the writer at his desk answers a voice that questions him about family, faith, deportation, and the themes in Se questo è un uomo; a university classroom in the Sant’Eufemia complex, where Levi, in the role of chemist and teacher, speaks to the public seated at desks about the close relationship between chemistry and writing, communication and translation, his “marginal” work experiences, the camp, and the “transmutation of matter,” also drawing from Il sistema periodico; and finally, the council chamber in the heart of the city, where the audience takes their seats and freely asks the Levi-witness, in the center of the room, the 22 questions printed on a sheet given to each, in a repetition of the testimony exercise that Levi devoted years to, culminating in his work I sommersi e i salvati.

The fusion between actor and character is such that during the performance, there is an increasingly unsettling feeling of being in the presence of the very Primo Levi, in a fast-reverse that takes us back fifty years into the super-real suggestion of hearing live from a survivor of the camp, still “young” and in the full process of reflection. Moreover, the technique of remote acting, where throughout the performance the actor receives live directions via earpieces from director Luigi De Angelis, further amplifies the humanity and apparent spontaneity of the actor’s actions and voice, favoring a realism that again prompts reflection on the possibilities of transmitting/translating the memory of deportation in an era when the witness has disappeared.

••••••

Living the Voice. Se questo è Levi. Interview with director Luigi De Angelis and actor Andrea Argentieri, who recently received two Ubu Awards for Special Project and Actor under 35 for the three-part project Se questo è Levi by Fanny & Alexander, by Viviana Raciti | Teatro e Critica, December 17, 2019

“But it really seems like him…” This is heard from the audience, several times. The adherence to the model, the ability to become a tool, an amplifier of voices, expressions, memories— that seeming not to be oneself but something else: Andrea Argentieri takes upon himself the performative nature of Primo Levi in this tripartite project by Fanny & Alexander, directed by Luigi De Angelis with dramaturgy by Chiara Lagani. But Levi, the subject, is not a fictional literary character, even if it is based on a historically verified foundation. The Levi to whom constant, inescapable reference is made, is that composed physicality and the voice subtly colored by the dialectal inflection, that calm, rational, reflective tone, never tainted by hate. He is, indeed, the Levi witness, the Levi writer, the chemist. But above all, he is the Levi orator, whose writing, as Luigi De Angelis recounts, “derives strongly from orality,” from that need to tell, not to shut himself away, and to pass on his testimony, as he attested in La tregua (The Truce), in which Levi recalls that, from the interminable return journey, he felt the need to speak and share what had happened to him with anyone who happened to cross his path.

The site-specific conception of Se questo è Levi, originally conceived for three locations ideally linked to his biography, gives way to other places that, in a certain way, succeed in evoking those relational dimensions: the more intimate, almost homey atmosphere of the first stage (which in Rome had been set in the foyer of the Valle Theater), the conference-like setting of the second (a cold and modern room at Palazzo Mattei), and finally the more inquisitorial space of the third (a wonderful reading room at the Angelica Library). Each of these places corresponds to different sources, as mentioned before, referring almost more to those not directly literary: interviews (like the one with Carlo Gozzi from 1985, presented in the first part, Se questo è un uomo), documentaries (the final act, Sommersi e salvati, is based on a sort of interrogation conducted by a group of students from Pesaro, to whom Levi offered himself, and whose footage is now on YouTube). Of course, Levi’s work is also present, for example, in the second part titled Il sistema periodico (The Periodic System), which includes excerpts from the book of the same name.

The term “not directly” refers to the fact that even the most spontaneous speech of the author presents its own recognizable and constant structure, just as the written form had to recover the dimensions of orality. Regarding these transitions from one medium to another, it is Levi himself, as De Angelis recalls, who emphasizes the necessity not to betray the original form of the work, not to modify “the urgency of testimony,” in favor of the so-called “super-realism.” For example, when reviewing his correspondence with his German translator at the end of Sommersi e salvati, Levi declared that, especially for Se questo è un uomo, he wanted to consider what was, for him, a compromise—the translation—as “a form of tape recorder for my experience,” capable of recovering in written words the exact texture, quality, and precise correspondence of every single term spoken. Thus, this project “tries to embody this formulation of Levi, attempting to be as much as possible an antenna, a channel, to capture that orality that still resonates in the present.”

Thus, the idea of super-realism mentioned by Levi aligns well with many characteristics of this project, from the essentiality of the scenic elements—almost isolating the material even at the expense of everything else—to the use of “heterodirection,” understood here as a further passage of testimony. In this exponential stripping away, one might wonder where and how it fits, how and what the artist chooses in this seemingly narrow space, what it can rise above: but, answers De Angelis, “if we were to add superstructures, other poetics, the risk is that this form would reach the audience less directly. Everything must be kept—the stumbling, that precise mode of speaking. If we had used the superstructures of theater, that proximity would have been less strong for me. So, the idea, from a directorial perspective, was to focus on the architecture of the texts and locations; this simple assembly of the basic elements should have been enough, nothing more.”

But behind this essentiality lies a profound exploration of how to render the figure of Levi. Here’s how Argentieri describes it: “For me, from the very beginning, from what I would call ‘first listens’ rather than ‘first rehearsals,’ my goal was to ‘be inhabited by a voice.’ My first and only artistic decision was to make a lot of space, to be as welcoming as possible to whatever I perceived. The voice became like a fluid: from my ears it began to travel throughout my body, as if I too were becoming a tape recorder. I allowed my instinctive side to work a lot.” Let’s open a moment to discuss “heterodirection,” a working method typical of Fanny & Alexander, which consists of directing actors through real-time audio cues via earpieces: in this case, it is not only, or primarily, De Angelis guiding Argentieri, but Primo Levi himself, whose words are continuously fed into the actor’s ears, subjecting him to a constant sensory stimulus that transforms into a subtle but pervasive interpretive work. This is, therefore, a body/voice presence that “reacts to the impulse rather than starting to process a script,” for a practice that practically relies on repeated deep listening and prolonged observation of videos, in order to absorb as much as possible the gestures, movements, prosody, and silences. “By combining the two, it’s inevitable that even at a muscular level, I almost feel his face, I try to make it rather than just feel it. I can see it from the expression of the people, who begin to look at me and listen to me with an attention that changes during the course of the marathon. I would describe it as a controlled meditation: I have control of it, but I leave a lot of space to give back and transmit everything I feel, the inflections, the pauses, the stumbles… It connects to a resonance in me: I don’t just hear it with my ears, but with my emotion, which I transmit all the time, without triggering that more rational part of the brain.”

De Angelis defines this practice as “inhabiting the voice,” which is able to recover “the soulful component, almost like the imprint of the spirit and psyche of a person. In recordings, many intimate issues are hidden; just as they are in our faces, even in the micro-variations in the filigree of the voice, traumas are hidden. It will never be a technical restitution.”

Especially in the third, interactive performance, Argentieri becomes a mediator between his voice, Levi’s voice, and the questions posed by the audience. Here, the 18 questions, presented to all on a sheet, become the basis for an ongoing dramaturgical construction, the order of which is dictated together, by the impulse of each spectator who chooses to wear, even if only for a moment, the role of the interrogator. Bathed in the preceding words, as if numbed by the presence of Levi, we accept the “as if” pact and no longer see the performance, but truly witness an interview, with real timing and rhythms. “I love those moments of suspension,” says De Angelis, “those moments of emptiness that are created for an instant. The pacing is given by the people, by the anxiety, by the speed of having to send the responses extracted from Levi’s writings to the console in response to the questions asked each time… All of this creates a very strong tension among everyone. You forget about the fiction, the initial contract that was made. It leaves room for another reception. It’s the place where we feel the most emotion, not only because of what we hear.”

We forget who we have in front of us, we forget the questionnaire, some people ask different questions, a very high tension is felt, as if so much else lingers in the air, that unspeakable thing on the brink of being questioned. I ask Argentieri: “Sometimes unforeseen events happen, as if they want to speak to his spirit, but I am very faithful to heterodirection and very respectful toward Levi. In those situations, I never improvise anything; everything must be related to the words he spoke. The first time, no one dared to ask question number 15, which asks if Levi ever considered turning his back on life. It has happened several times, there is a modesty, it creates discomfort every time. Once, in San Gimignano, we simulated Levi’s arrival during a press conference, and Daria Balduccelli (creator and curator of Nottilucente) posed the first two questions from Sommersi e salvati; a man, probably German, began to rant and shout at us, saying it was all in the past and buried, without realizing it was a fiction. Some women, on another occasion, asked me how I could have been in the concentration camps given my young age, thinking I had actually lived through them…”

••••••

Primo Levi According to Fanny & Alexander: The Author, The Witness, The Man, by Michele Pascarella | Hystrio – Trimestrale di Teatro e Spettacolo, October 27, 2019

Balancing between theater and performance, Se questo è Levi raises a number of unavoidable, fierce questions about and to society through the rigorous and disorienting recounting of events that are both extremely distant and yet very much present. The project, directed with a Socratic attitude by Luigi De Angelis, is conceived as a triptych: Se questo è un uomo (If This Is a Man), Il sistema periodico (The Periodic System), I sommersi e i salvati (The Drowned and the Saved), drawing from the titles and themes of the first, fifth, and last works of the author. It is meant to inhabit three spaces of common life (in our case, a library, an organic farm, and the City Council Hall of Albenga) in order to give voice and body to the stories, to History.

Using hetero-direction, a device that Fanny & Alexander has been experimenting with for about fifteen years to question the perception and consistency of what is given to be seen on stage, Andrea Argentieri allows himself to be “crossed” by numerous discourses, gathered from documents and audio and video interviews from the RAI archives, of the famous writer, partisan, and Italian chemist, giving back his three souls through an eloquence that is simultaneously assertive and punctuated with stumbles, energetic and full of syncopated pauses.

The “super-realism” that characterizes Se questo è Levi, made possible by the interpretive willingness to act as a vehicle for what is heard in the headphones, like a sort of transparent and consistent tape recorder, is constantly challenged by protean displacements: an old typewriter placed next to a laptop on stage in the first episode; a moment in which the protagonist deliberately abandons the Turin accent of the “character” in the second, and so on. The role of the spectator changes: initially a passive witness, they become, in the third episode, an active subject, engaging in dialogue with the protagonist. Chemistry and work, both in the factory and in the detention camp, progress alongside writing in this moving discourse, a form that the Ravenna-based ensemble has often explored and practiced, and which now seems to achieve exactly what it aims to “describe, with the utmost rigor and the least clutter”: as Primo Levi would have done. Well done.

••••••

“Se questo è Levi” by Fanny & Alexander, by Maria Dolores Pesce | dramma.it, September 13, 2019

It took part in all three days of the Festival, a show by its very definition itinerant in time and space, and in my opinion, it was the most interesting and intense event of the entire Festival. A complex dramaturgical movement built almost like a musical staff, or rather like the table of the “Periodic System of Elements,” as an echo captured from the existential, ethical, and aesthetic journey of Primo Levi. However, its final and intimate purpose seems to be to transcend itself syntactically and linguistically, as a dramaturgy, going beyond or rather revealing itself fully as an appropriate container of a sincerity that, in the broadest sense, transcends it. Each movement is almost a pause, a whirlpool, in the flow of Primo Levi’s existence, marked by the time of his writing, from Se questo è un uomo (If This Is a Man) to Il sistema Periodico (The Periodic System) and finally to I sommersi ed i salvati (The Drowned and the Saved). The hand of the playwright selects and restructures these works in different syntaxes with a participatory care, making it their own without betraying it in any way. The most hidden aspects of Primo Levi’s search emerge clearly: he was a chemist before a writer, as he himself emphasized, but above all, he was an “organic” intellectual in the highest sense of the word, striving for the surgical and almost scientific clarity of the discourse on humanity, beyond the rhetoric that suffocates it, and towards the awareness that should ultimately liberate him. All of this is appropriately emphasized by the environments chosen to immerse us in his discourse and words: the private study for the video interview at first, the laboratory later, and finally the council hall, the institutional space where an attempt at shared and community elaboration takes place. Places that, instead of creating an alienating distance from the aesthetic perception, emphasize its capacity for translation and metamorphosis from appearance to reality, and thus to the sincerity that overlaps life and theater. A work that is intense, engaging, and at times moving, and precisely because of its unusual historical and historicizing perspective, of extraordinary, unfortunately once again, relevance. A relevance that Primo Levi’s words present as a continuous warning, because at the end of the chain of intolerance lies the concentration camp: “It is the product of a worldview taken to its consequences with rigorous consistency: as long as the conception persists, the consequences threaten us.”

Within this surprising aesthetic journey, Andrea Argentieri, excellently directed by Luigi De Angelis, is brilliant in literally taking on the mental and emotional figure of Primo Levi, almost transfiguring his own presence into that of the lost writer, to recover it in the here and now of the stage, almost astonished.

••••••

••••••

“Se questo è Levi” by Maddalena Giovannelli | Stratagemmi, March 28, 2019

The challenge of reproducing reality – and the awareness of its impossibility – has always been one of the obsessions of thinkers and artists. Is it possible to strip away all the embellishments and return reality, even in its brutal and anti-aesthetic aspects? Or is it inevitable to alter and distort it? Primo Levi, among many others, also pondered these themes. In his dense correspondence with the German translator of Se questo è un uomo (If This Is a Man), Levi emphasizes the need to not betray the burning horror of the facts with words: “I was driven by a scruple of super-realism,” he recalls, “I wanted nothing of those harshnesses to be lost in the book… it had to be, more than a book, a tape recorder.”

From these reflections, Se questo è Levi was born, presented by Fanny & Alexander during the second weekend of the 2019 Vie Festival. The image Levi chose to represent his drive for truth – to create not a book, but “a tape recorder” – has a striking similarity with the method of work the Ravenna-based company has followed for many years: heterodirection, meaning the transmission of audio tracks to the performer, who then reproduces them live to the audience. What better way, then, to honor Levi’s “super-realistic scruple” than to mimic not only his words but even his voice and mannerisms?

The project, conceived and directed by Luigi De Angelis, draws from audio and video documents in the Rai archive and is a true spiritual summons of Primo Levi. On stage, actor Andrea Argentieri embodies with impressive precision Levi’s posture and appearance, using his own body as a medium for the words and thoughts of the Turin intellectual. The performance has a three-part structure (the sections are titled after three of Levi’s works: Se questo è un uomo, Il sistema periodico (The Periodic System), I sommersi e i salvati (The Drowned and the Saved)) and is designed to be experienced in its entirety as a two-and-a-half-hour marathon, but also in individual segments. It is presented in non-theatrical venues – at Vie in the beautiful Palazzo Foresti in Carpi, and later in the Museum of the Deported at the Fossoli Foundation – and it is easy to understand the reasoning behind this choice: the stage is the quintessential place of fiction and emphasis, and it is ill-suited to the delicate act of mimicry envisioned by Fanny & Alexander.

In the first chapter of the trilogy, Argentieri appears and sits at a worktable that, with its “drawers and assorted stationery,” mirrors exactly the description given by Levi. However, De Angelis introduces an ironic twist, imagining that the conversation with Alberto Gozzi (who interviewed Levi in 1985 for RAI, and whose interview is presented in full in the first part of the performance) takes place via Skype. The violent dialectic between past and present is already active in Levi’s words, who imagines his desk divided between the southern side of the typewriter and the northern side of his word processor, “my current idol, to which I prostrated myself.” Skype is certainly not the only concession to the present in this reenactment: it is the audience, by being present, who constantly brings the spoken words to the “here and now,” and so the half-spoken comments, the smiles in response to Levi’s Sardinian humor, almost seem to interfere with the transmission of the track.

The potential for a vivid dialogue with a ghost, silently explored in the first two parts, becomes central in the third chapter: the audience, placed around the actor, can now choose which question to ask the Levi avatar, selecting from a list of questions. Levi’s reflections then explode into the present, so to speak, invading it, simultaneously confirming and denying the possibility of reproducing reality without altering it. In addition to the interference of the audience, there is a deeper one: that of the actor, who lends his body to the reenactment but cannot entirely eliminate his own personal physical, emotional, and psychic presence.

That subtle hesitation, that slight roughness in the voice – will it be in the track? And that small stumble, as a hint of emotion, which briefly interrupts the lines of Se questo è un uomo – is it Argentieri’s or Levi’s? But it is precisely the possibility of a deviation, that fracture which opens between reality and its copy, that transforms the inert testimony into life.

••••••

••••••

The Relevance (and Necessity) of Primo Levi in the Fanny&Alexander Performance, by Federica Angelini | Ravenna & Dintorni, October 12, 2018

An extraordinary operation in its apparent simplicity. The Primo Levi project by Fanny & Alexander is nothing less than this. In a hyperrealism that sees the talented Andrea Argentieri on stage in the role of the chemist, writer, intellectual, and witness that he was, Levi literally seems to come back to life, to testify. Argentieri succeeds in the difficult task of giving substance, voice, intonation, and gesture to a figure who changed the way we think, remember, and piece together our history, without betraying its depth, sobriety, and authenticity.

In a triptych that touched a private study, the Dantesque room of the Classense Library, and the Municipal Council Chamber yesterday (Thursday, October 11) in Ravenna, we were able to experience a material, intellectual, and emotional journey that brought back the depth of Primo Levi, highlighting his necessity and modernity.

It is pointless to deny that the passing of time, the distancing from what Nazism and Fascism were, of which the concentration camp – as he explains, having lived it – is the logical consequence, risks turning even testimonies like his into “school material.” And make no mistake, it is good for this to be in all schools. But the danger is that it could be listed among other “school materials,” losing its literary greatness as well.

Levi’s story is one without hatred, the story of a scientist, or rather, a technician, who approached words with the same precision, completeness, and essentiality as a chemist. Argentieri and Luigi de Angelis (director) capture this, the physical three-dimensionality as well as the intellectual dimension of Levi, without adding, without rewriting, but giving his words a living voice and thus returning them to their full completeness. In some ways, they compel the audience to become readers again, to revisit those pages perhaps read many years ago, now somewhat faded, and to do so together, in that mirror which is the theater, but outside of the theater.

“Everyone should see it” has become an overused and abused phrase, often used recklessly. But no, not in this case. Primo Levi’s work is foundational to our essence as democrats, anti-racists, Europeans, and secularists. In his thinking, there is the ability to combine political consciousness, civil engagement, existential reflection, and historical analysis, sentiment and intellect. There are no enemies in Primo Levi. There is a need to remember, to understand, without rhetoric, without emphasis, without prejudices even about the perpetrators, but driven by a clear need for justice, to fight against oppression, to defeat fascism in every form. Without turning anyone into a devil or a hero. And isn’t this perhaps what we all, now more than ever, desperately need?

••••••

••••••

The Row Over the New Superintendent at La Scala is Terrible, But Theatre in Milan is Experiencing a Golden Age, by Paolo Martini | Il Fatto Quotidiano, March 10, 2024

[…] But it is certainly what happens beyond the most well-known or established halls, often even outside the very physical spaces of the theatre, that gives the impression of an active cultural life among the city’s passionate spectator-citizens. A sort of institutional crowning of this phenomenon was the hosting, in the unusual setting of the municipal council chamber of Palazzo Marino, on March 6, of the touching performance Se questo è Levi with Andrea Argentieri, which Fanny & Alexander have truly perfected, without any easy winks at the present or post-television language.

It made a great impression on the approximately 150 spectators who managed to book in advance to find themselves in front of an actor who so effectively conveys the complexity of this writer-scientist-survivor. This event is part of the Stanze da Alberica Archinto project, which animates it, and Se questo è Levi also actively collaborated with the excellent Olinda association, which every summer organizes the beautiful festival ‘Da vicino nessuno è normale’ at the former Paolo Pini psychiatric hospital.

••••••

Argentieri as Levi’s Medium. Reviving the Horror of the Camps, by Walter Ronzani | Il Giornale di Vicenza, January 29, 2024

For the Day of Remembrance, La Piccionaia stepped out of the Astra Theatre to invade a public space like the council chamber of Palazzo Trissino, which on Saturday hosted the moving performance Se questo è Levi by the Fanny & Alexander company. The location was not chosen by chance, as it reminds the audience that in the past, in other legislative halls, racial laws were decided, deliberated, and imposed. The result is an intense experience that both moves and makes one reflect. The spectators settle in the council benches, each finding a sheet with 25 questions that were actually asked of Levi. The audience is invited to speak and ask one of these questions to actor Andrea Argentieri, who responds with the words Levi used in his interviews. In this interactive monologue, the actor is surrounded by the audience who questions him. He wears earphones through which recordings of Levi’s responses reach him, which he interprets live. It’s a complex exercise that the audience doesn’t notice. In fact, the only hesitations are those that the writer showed to his interviewers of the time, which the actor replicates in his “super-realistic” effort to faithfully convey his testimony. This doesn’t take away from Argentieri’s ability to be in tune with the audience, responding to spontaneous questions that come up off-script. Argentieri almost plays the role of a medium, allowing himself to be traversed by Levi’s words to give them form. This is all amplified by a commendable actor’s mimesis, passing through gestures and facial expressions, which manage to make the writer’s inner emotions come to life. It feels as though you are truly face to face with Primo Levi.

What strikes the most is his lucid analysis of the horror of the camps, which he describes with scientific precision, delving into the intimate essence of things. There are also fragments of private life, such as the memory of the song “Amado mio”, which was the soundtrack to his happy moments when he returned to life as a man.

The questions follow one another. One is brutal: “Did the things you describe really exist?” The response recalls that the duty of memory is a never-ending task. Among the many questions asked, one arises spontaneously: paraphrasing another great Jewish intellectual, Paul Celan, one wonders, “Who testifies for the witness?” In other words, who will take responsibility for this burden of tragic memories? Se questo è Levi answers implicitly, showing that memory is a collective act, which cannot be left to the individual victim, but is a responsibility of the entire community.