The Garden

- Concept, Direction, Dramaturgy, Video: Luigi De Angelis

- Costumes (Video): Chiara LaganiVocals: Claron McFadden

- Live Looping: Emanuele Wiltsch Barberio

- Sound Direction: Damiano Meacci (Tempo Reale)

- Video Performers: Andrea Argentieri, Mirto Baliani, Ilenia Carrone, Marco Cavalcoli, Mirko Ciorciari, Consuelo Battiston, Gianni Farina, Adama Gueye, Chiara Lagani, Bet Lihem, Joshua Maduro, Roberto Magnani, Fiorenza Menni, Mauro Milone, Marco Molduzzi, Stefano Toma

- Organization: Marco Molduzzi, Maria Donnoli

- Production: Fanny & Alexander / E Production, Muziektheater Transparant

- Co-production: Romaeuropa Festival, Klarafestival

- In collaboration with: Cosmo Venezia

“Why is suffering such a frequent subject in art? Are we nothing more than consumers of others’ pain, or is there really space in us for compassion? Is there a sublime beauty in suffering? An ambiguity? What are the stories of our time that resonate with this suffering? Should art absorb this call? Become its spokesperson? Doesn’t it risk being consolatory? What responsibility do we have in observing the suffering of others?”

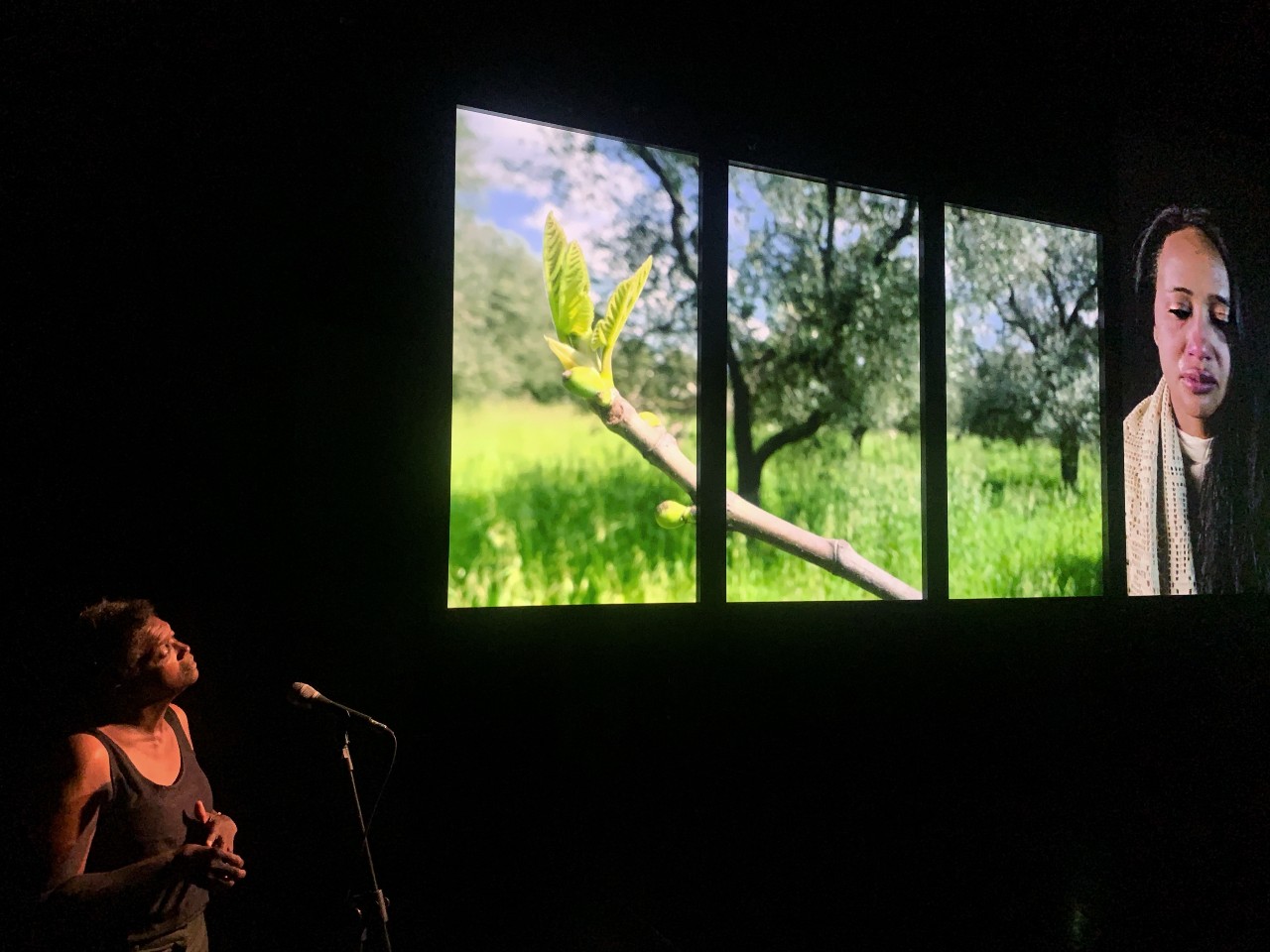

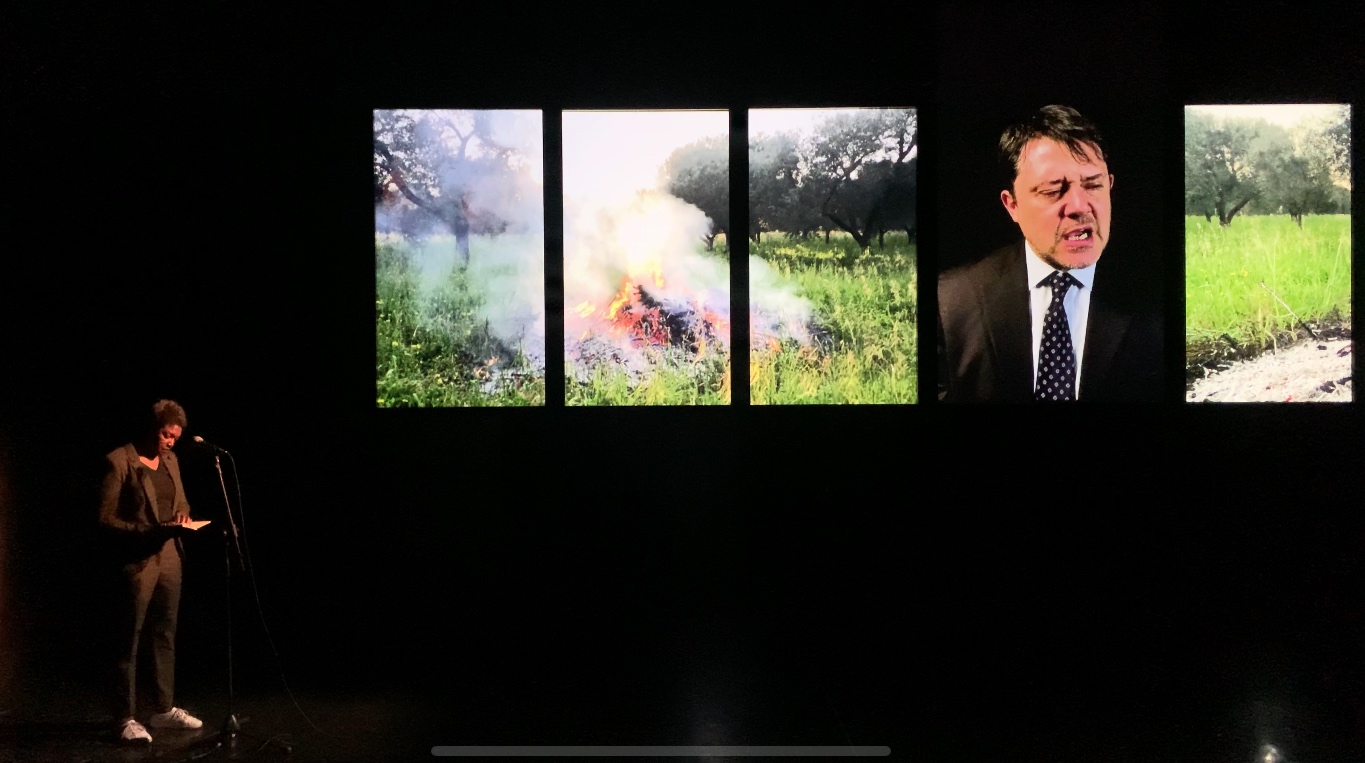

To try to answer these questions, Luigi De Angelis, together with Claron McFadden and Emanuele Wiltsch Barberio, creates a gallery of laments and musical memories from the past that evoke the theme of suffering in art: from Monteverdi to J. C. Bach, from Nina Simone to Giovanni Legrenzi, passing through Barbara Strozzi and John Dowland. Claron McFadden’s voice is the emotional witness of a video polyptych exploring the echoes of a contemporary Passion: seven Christological figures, inspired by recent news cases, along with other likely evangelical figures of our time, emerge on seven screens, in a progressive Via Dolorosa of gaze and perception.

Year : 2021

DEBUT

Romaeuropa Festival, October 9 and 10, 2021

Muziekcentrum De Bijloke, Gent, March 31 – April 4, 2022

O. Festival for Opera. Music. Theatre, Rotterdam, May 25 and 26

Ravenna Festival, July 5-6, 2022

November Music Festival, Hertogenbosch (NL), November 8, 2022

30F&A! Thirty Years of Fanny & Alexander, Atelier Sì Bologna, December 14 and 15, 2022

ph. Luigi De Angelis

Press Review

Luigi De Angelis’ installation-performance that blends Baroque and contemporary | Valentina Valentini, Artribune | October 27, 2021

The Garden by Luigi De Angelis is a multi-screen installation with live performance by singer Claron McFadden and live looping electronic music by Emanuele Wiltsch Barberio: a video installation/concert that “navigates between Baroque still life and a contemporary ritual,” enriching the repertoire of formats that have exploded beyond the proscenium in the 21st century—site-specific performance, performative architecture, bio-sculptures, living installations. On seven vertically aligned rectangular screens, faces of people—men and women—of different ages, are about to cry. The image moves slowly, with faces staring directly at the viewer, while McFadden’s voice delivers a repertoire of laments composed by Johann Christian Bach, Claudio Monteverdi, John Dowland, Nina Simone, and others in a layering of voices.

The images that appear on the seven screens of The Garden present portraits and landscapes, two formats stabilized in the history of Western art, as the landscape is the original place where all images gather, the intermediate place where the exchange between the inside and the outside happens, a subjectivity embodied in a face in which emotions and bodily reactions resonate as figures of the landscape. The author asks us: “What are the stories of our time that resonate with this suffering?”

On the seven screens, as many Christological figures inspired by political violence (tortures in Abu Ghraib prison, as well as killings in Afghanistan) coexist with figures inspired by the Gospel (Pilate, played by Marco Cavalcoli), in a landscape evoking the Garden of Gethsemane in Jerusalem, the Mount of Olives, where Jesus retreated after the Last Supper and from where he was taken to be crucified: a Passion updated for the 21st century. And what is our reaction to these daily tragedies: “Are we nothing more than consumers of others’ pain, or is there really space in us for compassion?”

During the 20th century, pain, once a shared experience within the community, progressively became a private matter, due to both the disintegration of the concept of community that also involved the intimacy of its members, and the medicalization of pain—and its shift to the sphere of modesty—through psychoanalysis and pharmacological therapies. As a result, the signs of the social representation of pain have been completely reformulated and often disappeared. In Observance (Bill Viola, 2002), the scene has the flavor of a funeral ritual, but there are no obvious causes for the pain: the individual, with their reactions, is simultaneously part of a group that does not present itself as a community, because each person is both crowd and individual, a single person part of a collectivity without any trace of belonging. This phenomenon is also present in The Garden, where the crying is singular, individual, not for the pain of the world.

In her essay Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag analyzes the iconography of suffering and observes that “torment, a canonical subject in art, has often been depicted in painting as a spectacle, something observed (or ignored) by others.” From photos of the Dachau and Hiroshima camps to the sculptural group depicting the torment of Laocoön and his sons, to the numerous paintings and sculptures representing Christ’s passion and the tortures of Christian martyrs, Sontag argues that these images tend to evoke emotional responses and excite the viewer as if witnessing a spectacle.

Shifting the focus to the theatrical scene, we observe that by the late 20th century, the stage anesthetized pain. In Greek tragedy (such as Hecuba, The Trojan Women), suffering often erupts as a result of dark forces, not voluntary acts, and finds an expressive channel through vocality, sonic gestures, and body postures. Meanwhile, the dramaturgy of the late 20th century, championed by Samuel Beckett, created a scene devoid of pathos, where, through insignificant and aimless actions, the physicality of emotions is pushed away into a sort of vanished world, or a relic surviving a storm. Hippolytus, in Phedra’s Love by Sarah Kane, represents a state of not feeling, not suffering, nor even enjoying. Even in the final act of his death, there is no space for emotion, except narcissism and spectacularization.

In The Garden, it is song that serves as the medium for suffering, rather than the images of people crying, which leave room for imagining the atrocities they have endured, the abuses, the tortures, as in the eponymous series by Andres Serrano. The video portraits in The Garden do not make suffering a spectacle to be observed—because pain is internalized through song, and the image is filtered through Claron McFadden’s voice. Because—as Corrado Bologna reminds us in Flatus Voci—“Before language begins and articulates itself into words to transmit messages in the form of verbal statements, the voice has always already originated, it exists as a potential for meaning and vibrates as an indistinct flow of vitality…”

It would be interesting to reconstruct the various representations of pain in relation to historical periods, geographical-social contexts, and gender, and create a visual-sound atlas of pain in the arts in the late 20th century and the New Millennium, uncovering the different gestures. As Salvatore Natoli writes in La politica e il dolore (Rome 1996): “The experience of pain becomes heterogeneous in itself depending on the epochal scenarios in which it occurs,” meaning that each era gives pain a different meaning.