West

Ubu Award 2010 for the best leading actress to Francesca Mazza

Audience Award 2010-2011 – Teatri di Vita

production Fanny & Alexander, Festival delle Colline Torinesi

concept Luigi de Angelis and Chiara Laganidj-set Mirto Balianidramaturgy Chiara Laganitexts Chiara Lagani and Francesca Mazzacostumes Chiara Lagani and Sofia Vanninidirection, set Luigi de Angelis with Francesca Mazzahidden persuaders Marco Cavalcoli and Chiara Lagani

Year : 2010

scenery and technical realization Nicola Fagnani (Atelier OperaOvunque) with Giovanni Cavalcoli and Simonetta Venturinitailoring Marta Beninipromotion and press office Valentina Ciampi and Marco Molduzzilogistics Sergio Carioliadministration Marco Cavalcoli e Debora Pazienzawith thanks to Ravenna Teatro – Teatro delle Albe, Davide Sacco

“West” is the outermost cardinal point in the story of the Wizard of Oz. The audience will be “imprisoned” together with Dorothy by a strange kind of spell, a trap of language which at times stops the faculty to express an opinion, the possibility to make a choice, to say yes or no to the things that will be proposed here.

The work, centred on the techniques of subtle manipulation of the advertising language, will intersect mythical themes to themes connected to contemporaneity, chronicle and the great emblems of the West.

Here the audience are consumers, the objects of continuous stimuli and the subtle plot of a concealed persuasion unceasingly weaved against them, the prisoners and, at the very same time, the ones capable of unhinging the cage in which they were dropped: carefully going down into the deep well where the trick of the “witch”, the sophisticated techniques of mass media communication precipitate, means undertaking the ascent and, at the very same time, taking the risk of not coming back.

“West” will be a sort of contradictory parable, a metaphor of contemporary imagery and its drifts, of the power that images exercise on us.

In the background the West and its symbols, and the tortured and yet incredibly “normal” body of our society.

TOUR

June 7-8-9, 2010 | Turin, Cavallerizza Reale, Festival delle Colline Torinesi (world premiere)

July 29/30, 2010 | Dro (TN), Sala Mezzelune, Centrale FIES, Drodesera

September 3, 2010 | Segni (RM), Capanno Culturale, Contemporanea – Segni Teatrali

September 10, 2010 | Rome, La Pelanda, Short Theatre

October 22, 2010 | Pisa, Cinema Teatro Lux, Teatri di Confine IV

October 27-31, November 2-5, 2010 | Ravenna, Ardis Hall, Nobodaddy 2010/2011

November 13-21, 2010 | Milan, Teatro I

February 3/4/5, 2011 | Rome, Angelo Mai Altrove

February 11/12, 2011 | Scandicci (FI), Teatro Studio

March 9/10, 2011 | Bologna, Teatri di Vita

March 16-20, 2011 | Naples, Galleria Toledo

March 22, 2011 | Ortona (CH), Teatro Comunale, Respiri di Scena

March 24, 2011 | Urbania (PU), Teatro Bramante, AMAT

July 22, 2011 | Motta Baluffi (CR), IL Grande Fiume

July 30, 2011 | Volterra (PI), Carcere di Volterra

September 23, 2011 | Forlì, Deposito ATR, Ipercorpo

November 24-26, 2011 | Ravenna, Artificerie Almagià, Nobodaddy 2011/2012

January 31, 2012 | Bolzano, Teatro Comunale

February 17, 2012 | Castel Maggiore (BO), Teatro Biagi D’Antona

March 21, 2012 | Lugano, nuovostudiofoce, LuganoInScena

April 15, 2012 | Bologna, Teatro delle Celebrazioni

May 6, 2012 | Montescudo (RN), Teatro Rosaspina

July 4, 2012 | Milan, Teatro La Cucina, Olinda, Da vicino nessuno è normale

July 28, 2012 | São Paulo, Brazil, SESC Belenzinho

August 3, 2012 | Castelfranco Veneto (TV), X-informadifestival

October 6, 2012 | Florence, Limonaia di Villa Strozzi, Tempo Reale Festival

February 7/8, 2013 | Bastia (Corsica), Fabrique de Théâtre

September 12, 2015 | Solofra (AV), Lustri Teatro

May 6/7, 2017 | Rome, Angelo Mai, F&A25

PRESS REVIEW

- Alessandra Vindrola, Fanny & Alexander – Our Journey through the West of Words

- Roberto Canavesi, West

- Franca Cassine, “West,” Dorothy’s Hidden World

- Osvaldo Guerrieri, The Wizard of Oz Hears Voices and Ends up in the Asylum

- Simone Arcagni, West by Fanny & Alexander

- Carlo Orsini, Small Pieces of Theater

- Elisa Scattolini, Communication, New Power

- Roberto Rinaldi, Fanny & Alexander Shake the Consciences of Humanity

- Rodolfo Sacchettini, The “West” of Fanny & Alexander

- Simone Nebbia, On the Penultimate Day at Short Theatre: Desires of a Sentimental Atlas

- Anna Bandettini, The Manipulated Language of Fanny & Alexander

- Matteo Antonaci, Short Theatre 2010

- Alessandra Cava, West by Fanny & Alexander

- Marco Palladini, West of the Wizard of Oz

- Laura Bevione, The West of Dorothy

- Erica Bernardi, Thirst Is Everything. The Image Is Nothing

- Alessandro Fogli, Oz and the “West.” What an Ending for the “Saga”

- Federico Spadoni, When Music Blurs into Theater. Mirto Baliani, the Sound of the Plot

- Franco Quadri, The Great “West” of an Otherworldly Diva

- Martina Melandri, West. Between Occult Persuasion and the Power of Imagination

- Franco Cordelli, Neuroses (and Boredom) in the West

- Kurt Kaplan, The Horizon of Voice: “West” by Fanny & Alexander

- Alessandro Fogli, The Ubu Prize 2010 to Francesca Mazza of Fanny & Alexander

- Massimo Marino, Francesca Wins an “Oscar”

- Roberto Rinaldi, Francesca Mazza Wins the Ubu Prize for Best Actress 2010 with West

- Vincenzo Branà, Francesca Mazza’s Dorothy Seduces Theater Critics: The 2010 Ubu Prize Is Hers

- Nicola Arrigoni, The Ubu Prize to Francesca Mazza: Theater Speaks Cremonese

- Tiziana Cusmà, O-Z WEST by Fanny & Alexander at Angelo Mai

- Alessandra Bernocco, Dorothy, a Prisoner of Images

- Massimo Marino, Phantasms

- Emanuela Ferrauto, West

- Nicola Arrigoni, With Francesca Mazza, the Present Is a Sentence

- Pietro Piva, LISTENTOTHIRST

- Jimmy Milanese, West, Francesca Mazza and the Fascination of a Choice

- Loredana Borrelli, West, a Journey Through the Imagination

- Giulia Tirelli, West, or the Death of the Image According to Fanny & Alexander

Alice No Longer Lives in Wonderland, by Pier Giorgio Nosari, L’Eco di Bergamo, April 4, 2005

Fanny & Alexander – Il nostro viaggio nel West di parole, by Alessandra Vindrola, La Repubblica – Torino, June 6, 2010

They are among the “oldest” guests of the Festival delle Colline. A paradox, as they are barely older than many newcomers. Nevertheless, the theater of Fanny & Alexander—an “art workshop” founded in Ravenna by Luigi de Angelis and Chiara Lagani—boasts a long history: nearly twenty years on stage and over 50 productions, including shows and videos. The secret of this unique combination of the company’s age and that of its founders lies in the fact that their partnership was born at school: they were sixteen when they met and have been creating theater together ever since. Their story is original, and their theater even more so—often described as “baroque.” The Festival delle Colline has embraced them, initially presenting their productions and later co-producing their latest work inspired by The Wizard of Oz, a series of eight performances culminating in West, which will debut at the festival tomorrow at 7 PM (Cavallerizza Reale) and will run again Tuesday and Wednesday at 9 PM.

But what does “baroque theater” mean? “We feel baroque in spirit,” explains Chiara Lagani. “Our work isn’t purely aesthetic. It’s an idea to be understood deeply, linked to complexity—the delight of unraveling folds, of delving into the hundred questions behind everything. That’s why our productions tend to be ‘colossal.’ This approach contrasts with the simplicity of binary alternatives, where everything is black or white. This logic is imposed on us, even in politics and fashion: it’s easier to control simplicity, which forces people to take sides, than to manage those who ask too many questions.”

Does this apply to West as well? “Especially to West, as it centers on two concepts: flow—a typically Western idea—and manipulation.”

How does this tie back to The Wizard of Oz? “The Wizard of Oz is part of our family lexicon. I think it’s one of the first books I ever read. It represents a return to origins. This series of performances revolves around the archetype of the journey. Ideally, before concluding this journey, we explore the four cardinal points, with West as the ultimate destination. It’s also a journey through linguistic codes; at the heart of the performance is the manipulation of advertising language.”

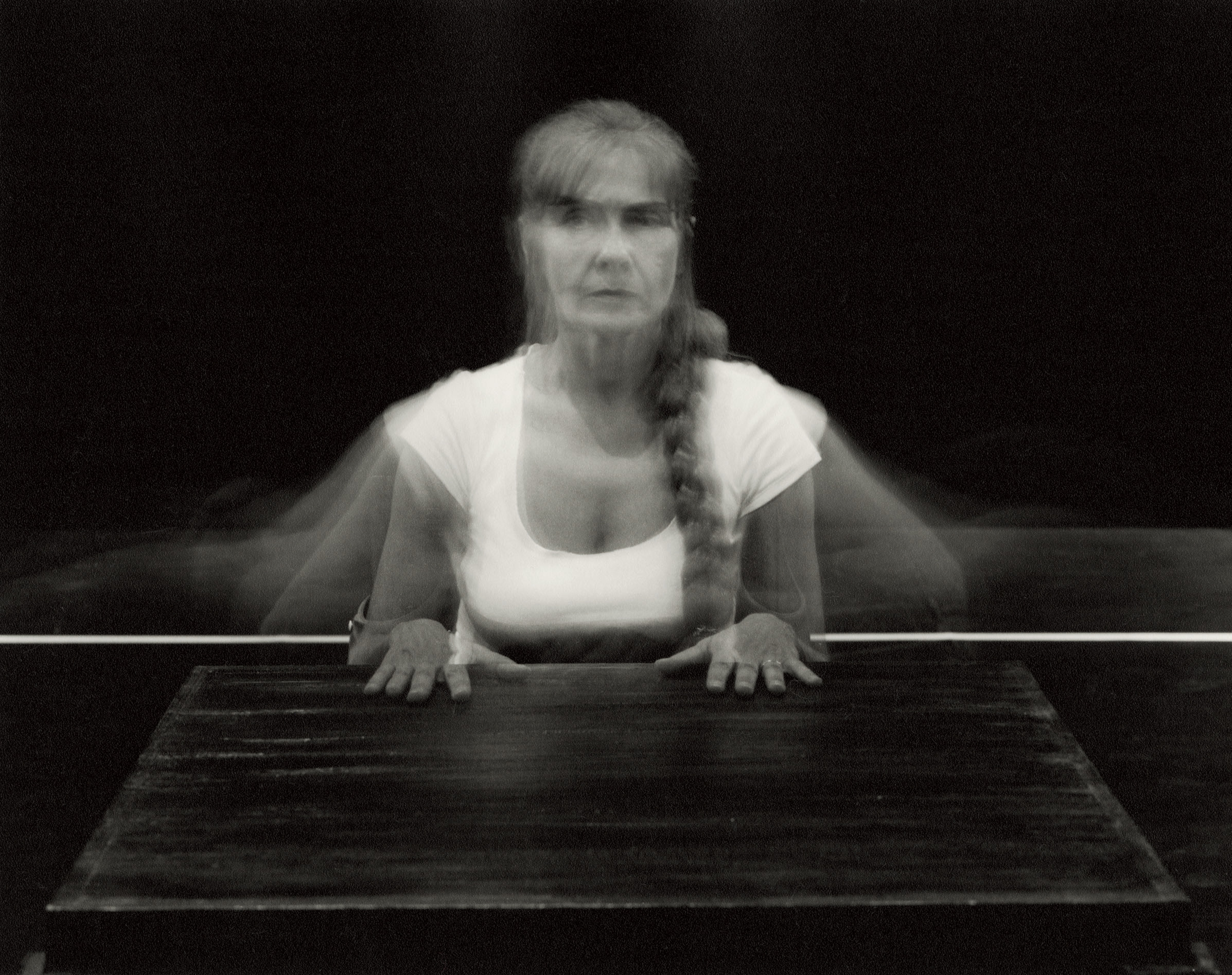

Yet West is a sparse production, featuring just one actress, Francesca Mazza. “Dorothy is an avatar, so each performance has been portrayed by a different actress, including myself. But each time, the show is built on the actor’s own experience. In this case, the actress on stage receives commands via two microphones from two distinct voices—one instructs her to perform physical actions, and the other gives verbal directives. Her responses to this subtle persuasion, gradually unveiled to the audience, create an unpredictable score that changes each time. In this, we all—audience included—retain some freedom: the way we react, the way we fill the gaps between moments of fullness and emptiness.”

The Wizard of Oz Hears Voices and Ends Up in the Asylum

By Osvaldo Guerrieri, La Stampa – Turin, June 9, 2010

Fanny & Alexander is one of the most loyal companies to the Festival delle Colline. It feels as though there’s a bond between these intrepid experimenters from Ravenna and the festival directed by Sergio Ariotti—a bond that transcends artistic respect and veers toward a love affair. This year, at the Cavallerizza Reale, Fanny & Alexander presented West, the final chapter of their long exploration into The Wizard of Oz, the 1939 film by Victor Fleming that introduced the world to Judy Garland’s grace and talent. At the time, she was little more than a child, playing Dorothy Gale, the figure at the heart of Luigi de Angelis and Chiara Lagani’s visionary theatrical journey. She is the totem of imagination, a figure who, above all, sees the glory—somewhere, of course, “over the rainbow.”

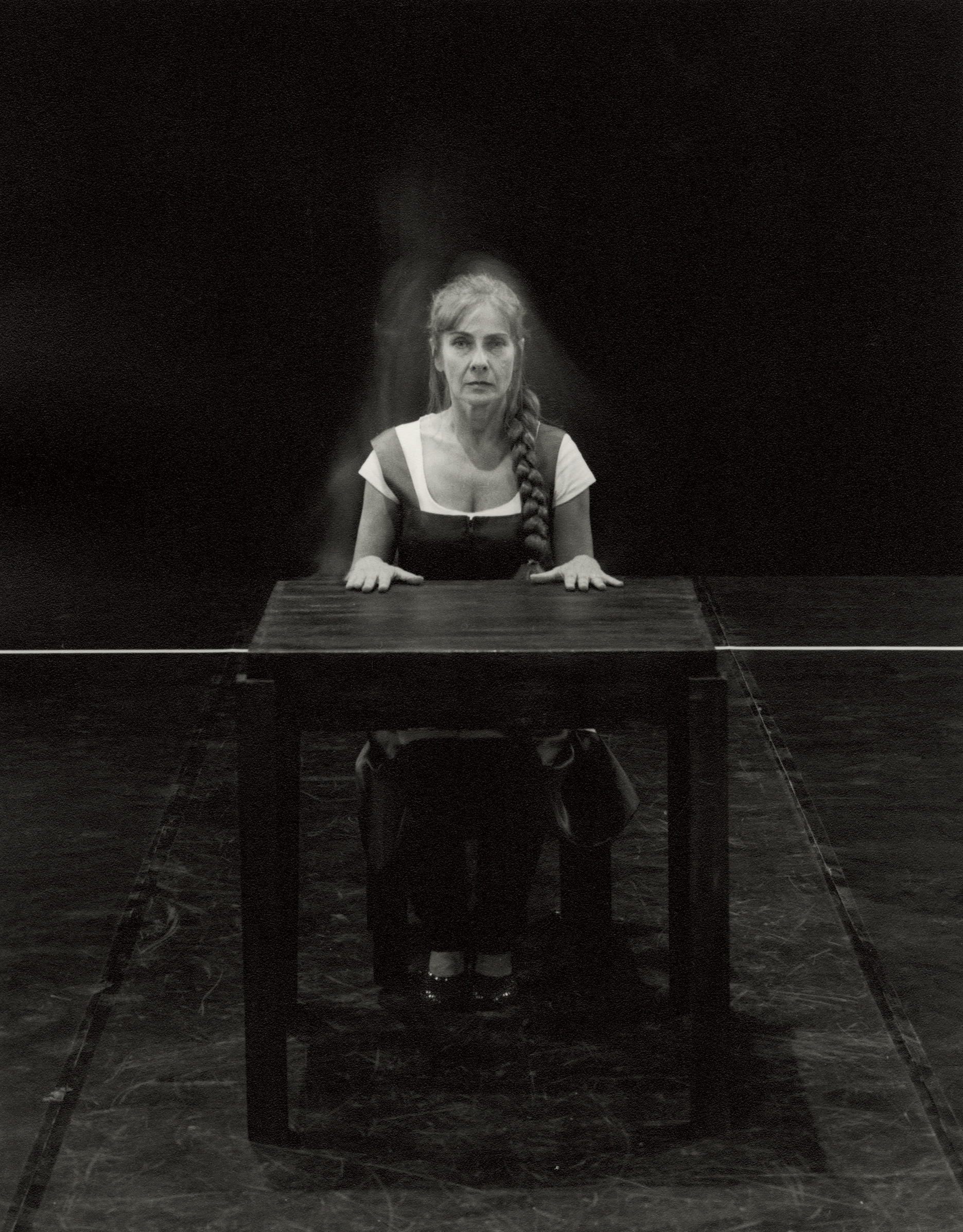

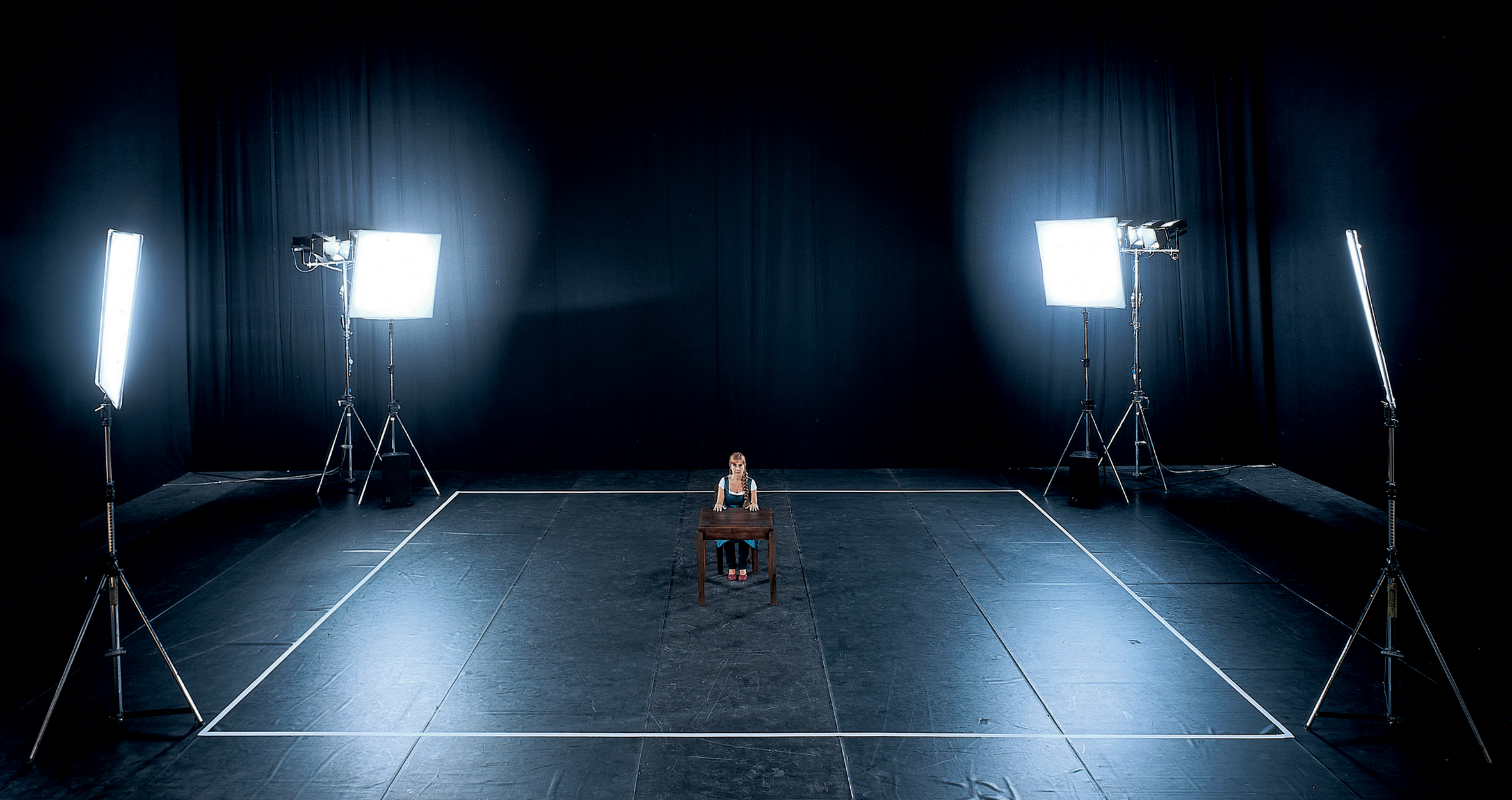

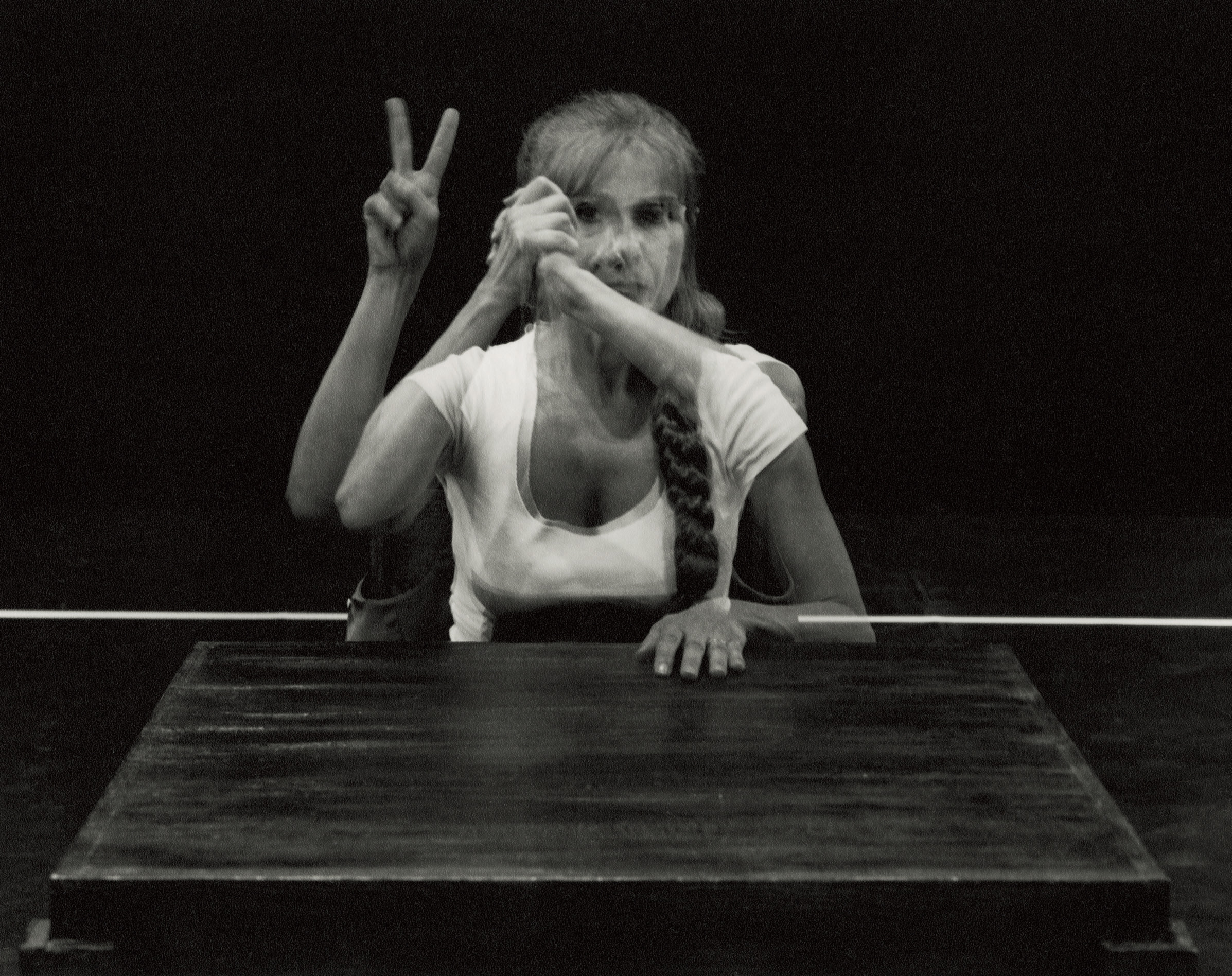

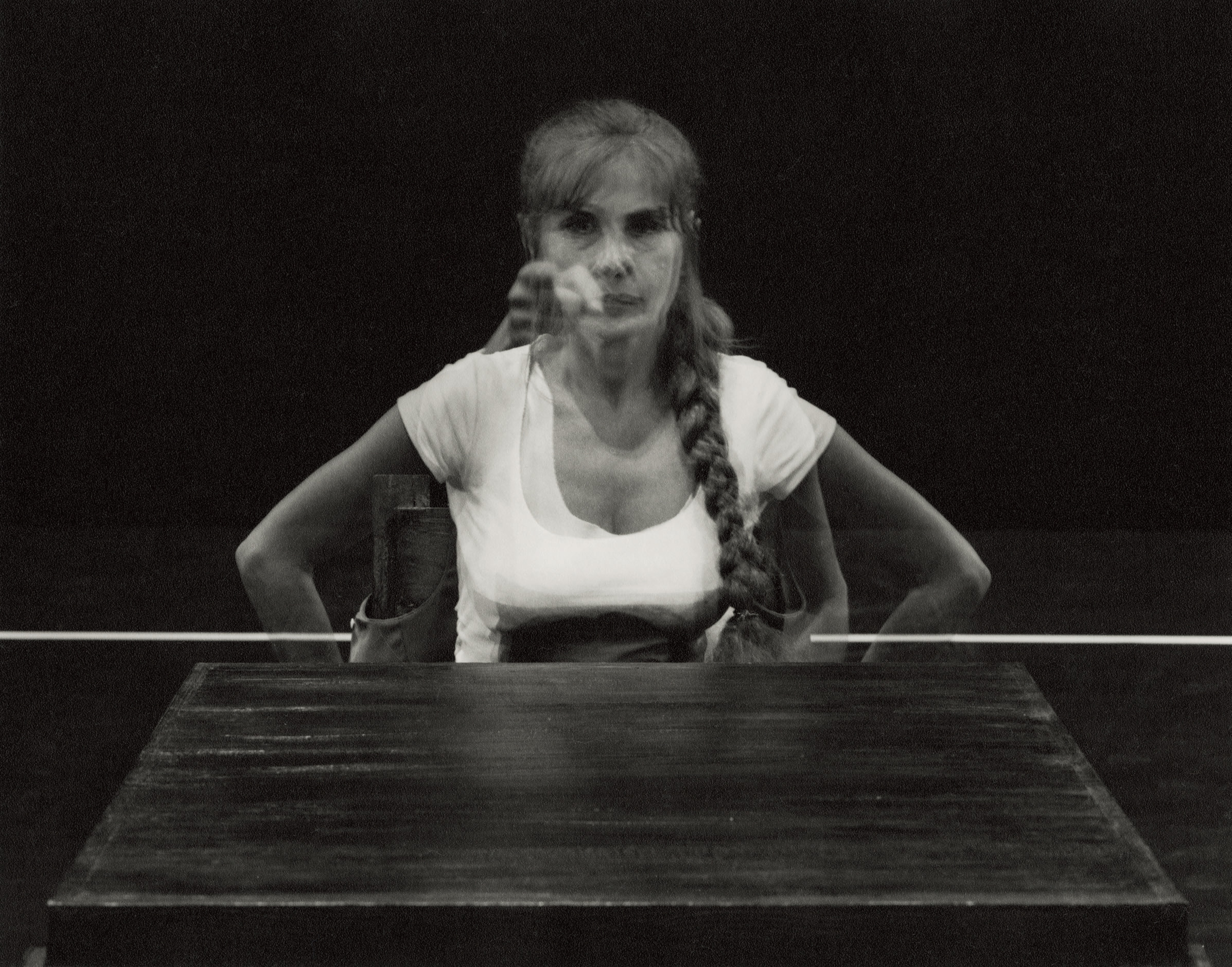

And so we arrive at West. This performance rests on the solo interpretation of Francesca Mazza, who awaits the audience seated at a simple, bare table. She seems to be at the center of a boxing ring. Four fixed lights illuminate her from each corner and never change. The actress drums her fingers on the tabletop and continuously presses her red shoes against invisible pedals. These are the initial signs of something resembling agitation. Percussive and piercing sounds arrive, overlapping at times and swallowing the performer’s words. She persistently asks, as if conducting a futile investigation, “Who is the most forgotten actress in history?”

Emerging from the overpowering soundtrack (or “scenophony,” as some might call it), two voices begin to torment the solitary figure. They issue commands and feed her lines. Gradually, this unnamed character adopts the behaviors and emotions imposed by these external prompts. She narrates stories of her life—banal on the surface but deeply disturbed and obsessive. It becomes clear that this solitary figure is a prisoner of herself, battling ghosts, possessed by a deranged mind. She is no longer Dorothy but Judy Garland, destroyed by alcohol and barbiturates.

In West, what matters is not what is said but how it is said. Form triumphs over substance. Francesca Mazza excels at maintaining the timing and rhythm of a performance that leads to dissolution. While the production may lack groundbreaking innovation (a potential limitation for a company that thrives on pushing boundaries), its execution is flawless.

West by Fanny & Alexander

By Simone Arcagni, Il Sole 24 Ore, June 10, 2010

West—a cardinal point turned into a reflection on a world choreographed through tics, gestures, questions, and tensions. A bare stage, a table, a chair, an actress, four visible spotlights fixed on her. Constant rhythmic music, a voice offstage issuing commands, engaging in dialogue, an unending stream of words and repetitions. It is a choreography of words, music, gestures, and refrains, constructing an imaginary rooted in the cardinal points and extending westward—toward the West, toward the Occident that is not just us, but especially America.

The new production by Fanny & Alexander, which I saw yesterday at the Festival delle Colline Torinesi, is taut, vibrant, at times schizophrenic—and utterly beautiful. The flow of words and underlying texts is hypnotic, pushing our “connectivity” and our disposable, pop culture mythologies to the extreme. Fanny & Alexander achieve this by once again placing a mythical prototype—The Wizard of Oz—at the center of their work.

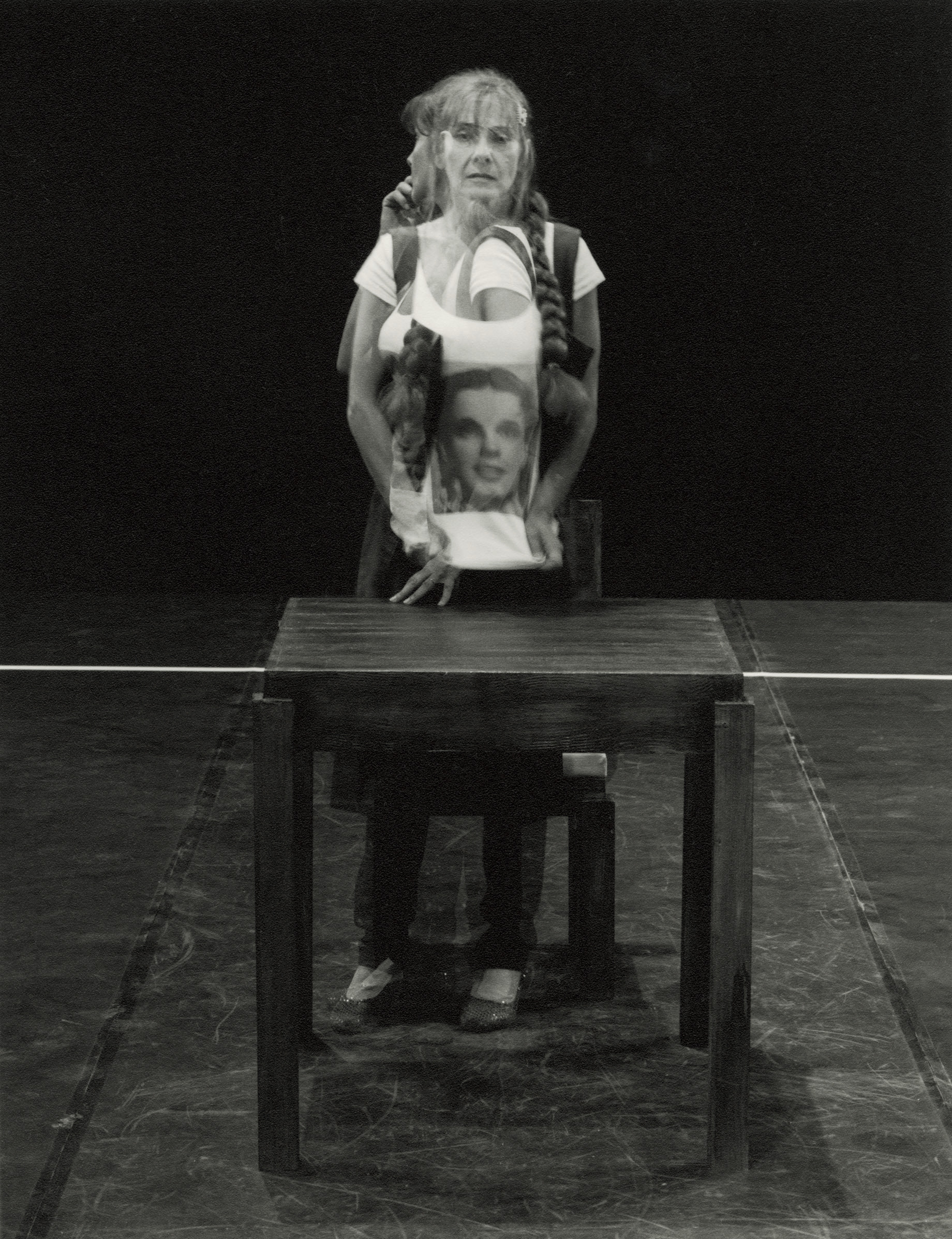

The actress, wearing Dorothy’s ruby-red shoes and a t-shirt emblazoned with Judy Garland’s face, receives instructions on her movements and words. She becomes a channel for hidden persuaders, immersed in a communicative flow, ensnared by the spell of unanswerable questions, trapped in a web of communication devoid of coherent meaning.

Small Pieces of Theater

By Carlo Orsini, Rolling Stone, June 2010

Eternally adolescent and intellectually gifted, Fanny & Alexander, the theater company from Ravenna, has spent the last two decades thriving in the realm of innovative theater.

Their productions are marked by deep intellectual engagement and a sharp plunge into the texts they reinterpret, alongside a speculative focus on sound and inventive staging. Memorable examples include the dark cone that trapped the audience in Vaniada, an episode from the Ada or Ardor project inspired by Nabokov; the school desks with notebooks in Alice vietato > 18 anni (Alice, forbidden > 18 years); or the audience lying on the stage in Dorothy. Sconcerto per Oz, the first installment of their ongoing Wizard of Oz project. This project has now reached its final chapter with West, premiering at the Festival delle Colline Torinesi (June 3–23), having previously explored Oz’s topology through the cardinal points, Emerald City in 3D, and There’s No Place Like Home–Kansas as a Museum of the Gaze.

Their powerful creative bulimia—driven by the demand for exclusive premieres at the many festivals they attend—often fragments their productions into multiple installments, sometimes at the expense of a fully realized understanding of the overarching project.

Amid this constellation of rarefied textual, auditory, and scenic references, their performances often suffer from lapses in tension, straying into an absence of effective “entertainment.” O-Z is now also a publishing project, released by Ubulibri, much like their earlier Ada: A Theatrical Novel of Riddles in Seven Homes.

The absolute cornerstone of the company is Marco Cavalcoli, a powerful-voiced actor who, in some episodes of O-Z, appears dressed as Cattelan’s kneeling Hitler and, in HIM, delivers an exhilarating vocal performance embodying all the characters from the Wizard of Oz film.

Communication, the New Power

By Elisa Scattolini, Corriere dell’Arte, June 18, 2010

With West, Fanny & Alexander conclude their series of productions inspired by the world of The Wizard of Oz. However, do not expect Baum’s Dorothy, nor the ornate joyfulness of the film version with Judy Garland. Here, Dorothy is a 52-year-old woman, alone in her battle against the image.

“What is the most outdated character in the play?” begins the protagonist, throwing her war cry—both anathema and plea for help—toward the audience from her seat at a simple table. “Put on the shirt, please,” she continues, her tone escalating compulsively. Starting from the premise of a strange experiment conducted on a group of volunteers, the show portrays the torment of a victim caught in the persuasive power of communication.

This modern Dorothy becomes increasingly bewildered, wrapped to the point of annihilation in the relentless suggestions of two “hidden persuaders”—the offstage voices of Marco Cavalcoli and Chiara Lagani. She is crushed by a language she no longer controls, as if bewitched by a spell that prevents her from mastering it.

Francesca Mazza delivers a remarkable performance, sustaining an hour-long monologue with great physical control, effectively conveying the protagonist’s growing unease. However, what doesn’t entirely convince is the choice to use the West from The Wizard of Oz to critique the dangers of communication’s persuasive power. It feels too “other” to serve as a metaphorical instrument, and inadequate to forge a symbolic connection between the agricultural West of late 19th-century America (as represented in the story) and the contemporary West, gripped by communication excesses, which is the focus of West.

The Manipulated Language of Fanny & Alexander, by Anna Bandettini, Post Teatro – repubblica.it, September 12, 2010

Among the theatre groups that emerged in the 1990s, Fanny & Alexander occupy a unique position. Because they are young (Chiara Lagani, Luigi De Angelis, Marco Cavalcoli are decidedly younger than other artists from that period); because they are an artistic workshop (in their city, Ravenna, the same as Le Albe), very lively, active, with a broad cultural outreach and the ability to weave meaningful encounters; and because they are also a prolific workshop, having produced some fifty shows, performances, and installations in twenty years. Their performances are complicated, challenging, difficult, and always have the power of surprise, capable of confronting the audience with unexpected questions, perhaps around archetypal figures, just as Alice by Lewis Carroll did many years ago.

For the past couple of years, Fanny & Alexander have been working on The Wizard of Oz, another archetype of our cultural universe. This work—also documented in a beautiful photo book by Ubulibri titled O/Z, which is exactly what the subtitle says, “An Atlas of a Theatrical Journey”—has been developed through seminars, workshops, residencies, and staged performances.

The latest one I saw is West, which debuted at the Torino Hills Festival and has now been performed in Rome at Short Theatre at Pelanda-Testaccio. On stage, the umpteenth Dorothy of this journey, a character that Fanny & Alexander consider to be the Avatar of the spectator in this journey with The Wizard of Oz. She sits behind a small square table at the center of an empty stage: from two microphones, she receives orders to make gestures and say phrases. The theme that, invisibly, creeps into this flow of words—at first appearing as a simple stream of consciousness—is manipulation, hidden persuasion, and the reactions it triggers in the individual who undergoes it but also in the one who witnesses it, the audience. As the manipulated verbal and gestural score progresses, it becomes increasingly fragmented, hiccupping, contaminated, nervous, anxious, and desperate, without the gestures or words ever managing (and here, too, high words mix with everyday phrases) to define a precise meaning or express a choice or a coherent thought.

Personally, I loved more the honorary, visionary work on Nabokov’s Ada, whose algebraic ambiguity found in the theatre of Fanny & Alexander multiple threads of images and meanings.

This piece on The Wizard of Oz feels more foreign to me, constructed. But what makes West exciting is Francesca Mazza, with her undone braid, her blue dress, masterfully managing body and words in that continuously fragmented, reformed, reinvented flow, turning it into a vibrant, hurried, warm verbal and gestural composition. Truly excellent.

Short Theatre 2010, by Matteo Antonaci, Exibart.com, September 14, 2010

West reflects on the drift of contemporary imagery and the role of the individual in the image-driven society. It is another step in the project that Fanny & Alexander has dedicated to The Wizard of Oz. At the center of a sparse, square stage, framed by a white ribbon and illuminated by four spotlights, actress Francesca Mazza sits with her face framed by a long blonde braid and sparkling red rhinestone slippers on her feet. “My name is Dorothy, I am fifty-three years old,” says the actress, plunging the audience into the world of Victor Fleming’s film. A world consumed, abused, destroyed, in which the little girl with blonde hair has become a mature woman, trapped in vortices of words and gestures that no longer belong to her. A perfect automaton, Mazza follows the commands given to her via two earpieces by Marco Cavalcoli (for the gestures) and Chiara Lagani (for the text). In her performance, almost cinematic, lies the ambiguous difference between imagination and reality, between media persuasion and individual will. Through the actress’s body and the image of an innocent Dorothy, Fanny & Alexander dissects Western imagery, letting it flow into a hypnotic sea of words embodied in the symbol of an America that produces dreams and icons. But Dorothy, the icon itself, soon becomes the pathetic image of Judy Garland, destroyed by alcohol and barbiturates.

West by Fanny & Alexander, by Alessandra Cava, Altre Velocità, September 14, 2010

West is not a direction. There are no signs pointing the way, nor golden paths to follow. Yet much travel takes place in this latest chapter of the O-Z project by Fanny & Alexander, within the West, enclosed within the fence of our thoughts: we run while sitting in our seats, we touch the boundaries with dance steps, we head toward no place. Every sign of the Wizard/Him, the clear superimposition of Cattelan’s Hitlerian icon onto Baum and Fleming’s “great and powerful” trickster character, seems to have vanished. We now find ourselves in a bordered, barren area, a square stage at the center of which sits Francesca Mazza, the avatar of Dorothy, exposed to full light as if nailed into the eye of her eternal cyclone. What is courage when one can no longer choose? How does one preserve their will? Dorothy’s West, this Dorothy who wants to learn how to say no, to not yield to hidden persuasion, to accept her own wounds, is a tight sequence of orders. Delivered by two “hidden persuaders,” the actress receives them through earpieces and performs them, creating with her actions and words a true score that follows the urgent rhythms of Baliani’s music. Automatic gestures, obsessive questions, clichés, slogans, fragments of Western imagery in which private memories and confessions intertwine, emerging clearly in the violent flow that sweeps everything along and breaks multiple times. Everything seems to have already happened, every illusion revealed. The mechanism, broken, is exposed on stage. “I’m here, I can’t do anything else,” the avatar repeats. “No place in the world is like this.” The audience, in the room that has remained always lit, waits for something they do not know and perhaps it will not come: the clicking of the red slippers will not take them anywhere. We are in the West, we are already home, and Dorothy is just one of our images to control at will. And Oz? The Wonderful Wizard is here with us, in its most dangerous, invisible, and insidious form beneath the threshold of every consciousness.

To the West of the Wizard of Oz, by Marco Palladini, Teatrica – www.retididedalus.it, September 2010

(…) After praising an excellent ensemble performance, I want to highlight a superb solo performance: that of Francesca Mazza, co-author and performer of West by Fanny & Alexander. Mazza, now 52, was, between the 1980s and early 1990s, Leo de Berardinis’s stage and life partner. So, following Leo, she received an exceptional education. She was already talented then, but in a subordinate role. Over the last two decades, her artistic growth has been extraordinary; she is now a mature, highly esteemed lead actress. In West, her acting performance is of an unusual scenic force, in addition to being of advanced theatrical technique. So much so that, as someone told me, it doesn’t seem like a show by Fanny & Alexander, the excellent Romagnolo group active since 1992, led by director Luigi de Angelis and dramaturg Chiara Lagani, known and appreciated especially for a brilliant creative flair in scenic composition, spatial-sonic research, and visual movement based on literary, fairy-tale, and meta-narrative pretexts.

This may be true: Mazza’s exceptional performance somehow overshadows the theatre of Fanny & Alexander, but they had the sense of measure and intelligence to take a step back. That is, they built around the actress a minimal, almost neutral container, with fixed lighting, and supported her acting exploit with small interpolations of ‘off-stage voices,’ instructions for use, as if they were the ones remote-controlling Mazza’s mimed stage journey instead of (as is evident) being sucked into her body-mind in action.

West is part of a multi-year theatre project by Fanny & Alexander on The Wizard of Oz, which over three years resulted in nine other productions. However, West is strongly intertwined with the personality and bio-artistic story of Francesca Mazza, who embodies an adult Dorothy (but with a childlike braid), projecting fragments of her personal history, happy impulses, paranoias, pains, obsessions, the highs and lows of a life in and beyond a theatrical career. For the entire first part of the show, Mazza sits at a small table facing the audience, as if trapped in a series of small, iterative movements of her arms and legs, suggesting a psychic compulsion manifesting physically. Mazza mixes shards of memory, joys, and angers from her own life, tangential thoughts on the world and society, with fragments of L. Frank Baum’s novel, where the West represents the most extreme cardinal point in the history of the “Wonderful Wizard.” Then the thoughts occasionally overlap, veer off course, get lost, and then are found again, and she accelerates the rhythm of her phrases, repeats them, intertwines them, varying them in a virtuosic and even schizophrenic crescendo that reminded me of Leo’s idea of a “free actor,” one capable of controlling improvisation like the champions of free jazz. Leo is also present, obviously, in the tumult of Mazza’s precordial and recited memories, but he remains unnamed, only mentioned as “a previous companion” in reference to an incident that de Berardinis personally told me about, involving a dramatic dog attack by the couple’s pit bull that ended up severing a fingertip of Francesca.

At one point, the actress breaks out of the ‘woman sitting’ cage and stands up, embarking on precise, meticulous, geometric paths on stage, associating a rigorous and asymmetric para-choreographic gesture with increasingly dissociated and divergent interpretive diagrams. This produces the effect of a finely calibrated contemporary musical score of acts and words. From what I saw and heard, it was the highest point, the apical moment of the festival.

The West of Dorothy, by Laura Bevione, Hystrio, no. 4/2010, October 2010

An experiment in hidden persuasion: this is how the new, hypnotic show by Fanny & Alexander presents itself, performed on stage by an actress and directed offstage by two “hidden persuaders,” namely Chiara Lagani and Marco Cavalcoli. A woman, sitting at a wooden table, evidently under tension, introduces herself, says she is 52 years old, recounts her first trip to the United States, and the planned second flight across the ocean that was canceled due to a suddenly aggravated, underestimated health issue. She then recalls anecdotes from her past: a minor car accident with unexpected consequences and an embarrassing stay with a colleague. These stories, however, are not linear but interrupted and resumed, interspersed with questions and reflections that repeat like unusual refrains. Meanwhile, the actress’s hands and legs are constantly moving, drawing short and dark trajectories. The protagonist then moves her chair to one side of the stage, delimited by a black line, and in the finale, she moves along that perimeter, performing the movements and speaking the words suggested to her by a female and a male voice. In this way, the device that underpins the performance is revealed, which determines its ever-changing, self-differentiating nature: Francesca Mazza, tireless and generous in exposing her human frailties, does exactly what she is told through two earpieces, one for each ear and one for each “persuader.” The actress, reincarnation of Dorothy, the protagonist of The Wizard of Oz, to which Fanny & Alexander’s work has explicitly been inspired in recent years, becomes the volunteer subject of an experiment on the possibilities of surreptitiously influencing our choices and decisions. But Francesca-Dorothy, although disciplined, knows that sometimes it’s necessary to say “no” and seems to manage to escape the persuasive power attempting to manipulate her like a puppet. An attempt that the West — the “West” — we inhabit has been carrying out for some time and which Fanny & Alexander invite us to counter with this rigorous and ruthless show that, using them, exposes those sophisticated persuasive techniques trying to shape our society.

Thirst is Everything. The Image is Zero, by Erica Bernardi, Paneacqua.eu, October 27, 2010

When the lights came on and I saw Francesca Mazza sitting in that chair, behind that table, at the center of the stage, I thought of the first frame from La Fille sur le Pont by Patrice Leconte. The film opens with a tribute to the most autobiographical film by master Truffaut, more precisely to the scene where the young Antoine Doinel, in a reformatory, is interrogated by a psychiatrist who asks him about his intimate life and difficult relationships with his parents, to which Antoine responds with disconcerting frankness. Leconte places the story and life of the fascinating Adèle (played by Vanessa Paradis) on the analysis chair. Adèle is also an unsettled girl: after attempting suicide by throwing herself off a bridge over the Seine and being saved by Gabor (Daniel Auteuil), a knife thrower, she has nothing to lose and agrees to be his target in his shows.

A love-hate relationship gradually develops between the two. This film is the story of a relationship outside the norm, undefinable, and of a continuous journey. It’s the story of a woman who cannot feel as loved as she wants, who cannot feel comfortable in any situation, who cannot make a choice, who cannot say no.

This is the case with the “most out-of-fashion character” that Francesca Mazza plays in this experiment, robotic, electric, driven by sound impulses. Her fingers drum, there is a lack of courage to say NO, in order to always feel loved, accepted. Fanny & Alexander try to outline the difficulty of making choices in our time, the difficulty of taking strong positions. And they tell us what happens when we can’t express any preference: when everything is for everyone, it’s as if giving nothing. “Only by expressing a preference will you be a giver.” You cannot reach everywhere, you cannot please everyone, you cannot do everything you would love to do. Few things, but with criteria, and decision. Because “people pay much less attention to us than we think,” this is the case with the audiences of our time who are not trained to see things that are not explained, not served in a media-driven way. They can’t surpass the step of perception (when perceiving is not the same as understanding) and they confine thought within the interstices of habits.

“Faire les quatre cents coups” (an idiom that inspired Truffaut’s film) in French means “to make a huge ruckus.” Francesca Mazza turns her whole body into a communication interface because “no place in the world is like this,” theatre tries to reclaim its subversive and revolutionary space. Theatre wants to dismantle the dominance of low-intensity rituals, the image that becomes the world.

The avant-gardes of the early 20th century freed art from the tyranny of meaning: today, the ethical function of art is more than ever to generate languages from things, materials, tools, and technologies, because it is in language that the schemes of human experience are drawn and the possibility to reflect on it. Theatre is the space where one wants to know how to say NO to that heavy social drug of the Western world called illusion.

The illusion of being anyone and everywhere, “periphery and center, intelligent and courageous,” the illusion of making “normal and exceptional choices.” That illusion that makes us neurotic to the point that our words (like Mazza’s words) always say the opposite of what our bodies say (like the actress’s body), in the constant pursuit of an image that we will never reach, continuing to thirst, always thirsting. Until there is no more water to drink. “In one minute, I will no longer be here, in one minute, I will no longer be here”: darkness in the room.

This is the West of Fanny & Alexander, a West of the apathetic who walk naked for eternity around an undefined sign, stung by wasps and hornets. A West of living corpses who don’t know how to act either for good or for evil, who can’t take a stand, who always conform, out of fear of not being loved or accepted. “Mr. President, I want to know how to say no.”

Oz and the “West”. What a Finale for the “Saga,” by Alessandro Fogli, Il Corriere di Ravenna, November 2, 2010

After a three-year period of eight works – “Dorothy. Sconcerto per Oz,” “Him,” “Kansas,” “East,” “Emerald City,” “There’s No Place Like Home,” “South,” and “North” – the Fanny & Alexander company reaches the end of its project centered around Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz with “West.” The logic behind West can be found in the very beginning of the entire saga, that formidable meta-theatrical big bang that was “Dorothy. Sconcerto per Oz,” where everything happened simultaneously and on multiple narrative levels – textual, chromatic, musical, and semantic – in an irreversible explosion of creation by parthenogenesis. From one to all, from Baum’s Dorothy to the nine Dorothys on stage.

Of those Dorothys, after a journey that touched all the cardinal points, only one reaches the West, but it is this single figure – an absolutely stunning Francesca Mazza – who bears the arduous task of closing the elliptical journey, bringing everything back to unity. This Dorothy sits at a simple wooden table within a square space marked by ordinary white lines. She seems to want to tell us about a certain experiment in hidden persuasion conducted in the West, while simultaneously sharing something about herself, events that happened, reflections. It is also evident that Dorothy, in addition to speaking about several disconnected things at once, also wants to move.

And she does. She does it neurotically, without coherence; her body seems autonomous from her mind. Her feet dance mute rhythms, one arm occasionally dusts the table, her face is prey to every emotion; the speech is syncopated, stuttering, restarting, mixing, scrambling logics and constructs, all over a dance track that is also incoherent. All of this happens because the experiment she wants to talk about is paroxysmally being imposed on her. Two hidden persuaders are manipulating her through the earpieces she is wearing.

Dorothy is simultaneously given two types of commands, one linked to a series of gestures and the other to a series of textual blocks, by a male and a female voice. The rhythm increases, Dorothy moves her chair along the sides of the square, then rises and strides along the perimeter; the commands – now revealed between the folds of the music – grow more insistent, creating an increasingly changeable score in which the mellifluous inputs of advertising language blend indistinguishably with the life of the protagonist.

Thus, the West is not a very nice place, and if we hoped that – for the first time – the absence of the enigmatic “controller” Oz (always looming in other episodes, at least iconically) would be a harbinger of newfound freedom, we were greatly mistaken, because Oz is everywhere here without the need to show himself. Oz is the very essence of West, he is, lying and false, the symbol of all the insidious powers at work in the West.

When Music Crosses into Theatre. Mirto Baliani, the Sound of the Plot, by Federico Spadoni, La Voce di Romagna, November 9, 2010

Imagine being an actor for a moment. You are alone on stage. You must act and you know the outline of the story. However, there is no fixed text, and the parts change each time according to two unexpected variables: the commands imposed by two “hidden persuaders” and the relentless pacing of a DJ set, the only element capable of dictating the transition from one scene to the next. I almost forgot: during the performance, you must follow the rhythm imposed by the beat with your hands and feet. If the feeling you would experience in the role of the protagonist is unease, given the uncertainty of the movements to be made and the words to be spoken, here is how the audience of Fanny & Alexander’s latest work (staged at Ardis Hall from October 27 to November 5) finds itself thrust into the enchanted world of West, captivated by the fears and uncertainties of the now 52-year-old heroine from The Wizard of Oz.

Experimentation and improvisation for a work in progress, built on continuous climaxes of voice and music, in which Dorothy (Francesca Mazza) and the spectral off-stage voices (Marco Cavalcoli and Chiara Lagani) bounce within the electronic mixes created by composer Mirto Baliani. This is why the second installment of this musical column strays into the world of theatre.

With Mirto Baliani, a 33-year-old originally from Rome but now living in Madrid, collaboration has become a constant for the Ravenna-based company. Eleven years of performances, none of which had ever reached such a level of musical improvisation, able to determine the course and duration of the performance itself. The idea came almost by chance, during rehearsals: “We realized that with a fixed soundtrack, something became rigid, and it lost the freshness of the initial idea.” Thus, the intuition emerged: use fear to energize the plot each time: “We noticed it every time we experimented with new tracks,” he continues. “The difficulty of not relying on the usual musical theme combined with the evolving text made the difference.” A turning point that follows the notes of composers considered gurus of the German electronic scene, such as Murcof, Apparat, and Burnt Friedman, along with a few tracks composed personally by Baliani. It is their shift from swing to drum & bass that accompanies Dorothy in her exploration of society’s contradictions, in a journey shaped by the DJ’s hands: “Reverbs and effects allow me to change tones, frequencies, and speeds at will,” he explains. “For us, it’s stimulating; for the audience, it’s an experience that can’t be replicated.” To confirm this, just look at the audience’s expression: between scenes, some heads turn to look toward the sound booth, almost as if asking, “What will happen now?”

The Horizon of the Voice: “West” by Fanny & Alexander, by Kurt Kaplan, MusicaElettronica.it, November 23, 2010

Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz is still alive and 52 years old: we discover this right away at the start of Fanny & Alexander’s theatrical work, the leading Ravenna-based company of Italian experimental theater. This Dorothy is likely still immersed in the imaginary whirlwind that captivated her in the 1939 film by Victor Fleming, based on the fantastical pen of Frank Baum. She is the only character in this engaging and virtuoso performance, brilliantly portrayed, with the help of two “hidden persuaders” who guide the actress through both her movements and the spoken text by providing instructions via earpieces on what to say and what actions to perform. They act, invisible to the audience, as true dramaturgical engines, interpreting and improvising a kind of textual-gestural score that is constructed moment by moment and, while formally defined, changes each night.

What results is a continuous flow of vocal sounds and gestures, with constantly changing and moving qualities, to which music adds an emotional layer through a continuous DJ-style mix of rhythmical fragments that intentionally lack identity. It is this metaphor of “flow” that leads the audience on an alluring and layered sonic and visual journey, reflecting on some of the crucial themes of what constitutes the “West” today—its inescapable connections to the United States, its slogans, its typical persuasive mechanisms, and its contradictions.

The technical process of the persuaders is revealed sparingly, and it is only halfway through the performance that one fully understands its mechanisms: this leads to a new reading of the time that has passed and, at the same time, to an interpretative clarification of the remaining portion.

A special mention goes to Francesca Mazza, who is able to decode and respond to many stimuli simultaneously, bringing to life a true “biological puppet”: the soul of Dorothy, forever imprisoned in the Western part of the world of Oz.

As one might expect, in such productions, technological precision is of primary importance, and it often happens that setups in venues not particularly equipped for sound limit the quality of reception. West seems to overcome these issues: its expressive power and deeply musical nature make it one of the best examples of new sonic theater.

The 2010 Ubu Award to Francesca Mazza of Fanny & Alexander, by Alessandro Fogli, Il Corriere di Ravenna, December 14, 2010

Once again, the Ubu awards bring great satisfaction to the Ravenna-based company Fanny & Alexander, who at the 33rd edition ceremony, held last night at the Piccolo Teatro, saw Francesca Mazza awarded Best Actress (nominated alongside Mariangela Melato, Federica Fracassi, and Arianna Scommegna), for her role in West (recently seen at Nobodaddy of Ravenna Teatro). It is a highly demanding role for the Cremona-born actress, who had already won the Ubu in 2005 as Best Supporting Actress with Fanny & Alexander, “forced” into a performance under constant guidance of two types of input—verbal and movement—via earpieces.

Francesca, a new Ubu award, and again with Fanny & Alexander. “The Ubu award for West holds many meanings for me, beyond the immense pleasure and honor of receiving such a prestigious recognition. One meaning, above all, is connected to my relationship with Fanny & Alexander. After the show, when people congratulated me on my performance, I always said that West represented the culmination of a love story with the company. It was a performance born in an extraordinarily harmonious way. I remember meeting Fanny for the first briefing about what they wanted to do with West on January 4th, and even at that meeting, everything was clear and well-defined. What they envisioned then was exactly what debuted in early June at the Festival delle Colline Torinesi. There was no deviation, no second thoughts—it was a very straightforward, serene working process, and I believe this is due to the many years we’ve been working together, with a deep understanding and intimate artistic connection, as well as a personal one.”

The personal aspect has a significant role in the performance. “Exactly. It is a very personal work, deeply built around me. And then, Fanny created this truly genius device, with which, through earpieces, they guide my actions and words in different directions at the same time! I often talk about it with my fellow actors: it was truly a unique experience, because after so many years of ‘training’ yourself to control your performance—intonations, gestures—they put me in a situation where I cannot exercise that control, where I do not have the time to do so, and thus, I work in a trance-like state. And it’s true that perhaps this is a state you can only allow yourself to enter after many years in the craft. I remember something Leo de Berardinis always said, that technique should be mastered to the point where you can forget it. Maybe this is a bit of an example of what it means to go on stage forgetting what you have learned while still making the most of everything you’ve learned. So, this trance-like state clearly suits me.”

Specifically, what were the biggest difficulties in portraying this role?

“There were essentially two main difficulties. I must confess that every evening, when I go on stage and find myself sitting at that table, I am always in a state of apprehension that is different from my usual one, and every evening I wonder if I will make it. Because, beyond the physical fatigue, it requires a very high level of concentration. During rehearsals, working for many hours with the headphones in my ears, I would reach the evening, in bed, still hearing the voices. You need to have your mind divided, going in two different directions simultaneously: making sense of the text you’re being given and performing specific actions in the moment and in the manner they are suggested. So there was a real difficulty in dealing with this pervasive way of being directed and, I must admit, also in accepting being essentially commanded. Of course, I knew this from the beginning, but sometimes I really felt rebellious. So from this point of view, it was a job that required great discipline. The other obstacle was related to the fact that Chiara Lagani prompted me with personal issues to compose the dramaturgy, and at one point I instinctively felt a sense of shame and unease at the thought that I would have to say them publicly, out loud. Then, I had a subsequent thought that helped me: questioning whether the things I was putting forward were truly mine. In reality, they are just episodes taken as examples of this difficulty in saying ‘no,’ because the theme of asking for the courage to say ‘no’ was central. And in fact, the audience’s reactions tell me that, beyond my personal story, this is a performance that concerns us all, that speaks about us in general. Because I believe that all of us have this problem regarding conflict, saying ‘no,’ and feeling commanded. From the reactions, I see that the audience doesn’t dwell so much on whether what I’m telling is personal or not, but in recognizing themselves in what they see and hear.”

Francesca Mazza wins the Ubu Award as Best Actress of 2010 for West, by Roberto Rinaldi, Teatro.Org, December 14, 2010

The award for Best Actress 2010 was given to Francesca Mazza. The jury of the Ubu Awards 2010 decided to honor the actress with this prestigious recognition for her intense performance as Dorothy in West, a production by the Fanny & Alexander company from Ravenna and the Festival delle Colline Torinesi, described as “the extreme cardinal points of the story of The Wizard of Oz.” Alone on stage in what can undoubtedly be called “The Actor’s/Actress’s Test,” she is almost hypnotically manipulated in terms of language and mass media communication. Two hidden persuaders force her into total submission, to which she cannot rebel, and consequently, the audience is “captured” and stimulated by a series of obsessive vocal impulses. It is a neurosis in which the entire contemporary society is poured, subjected to continuous sonic and visual stimuli from invasive and devastating advertisements.

Francesca Mazza’s commitment is such that she is recognized as an extraordinary talent, further enriched by her personal autobiographical contribution to the dramaturgy, written by Chiara Lagani. She confesses to feeling emotional right after receiving the award on the stage of the historic Piccolo Teatro in Milan during the ceremony, presided over by Gioele Dix and attended by many Italian theatre colleagues.

How did you feel when you received the award?

“It was a long ceremony, and Gioele Dix was fantastic in lightening the tension. It was a lovely celebration of theatre. I feel it as an encouragement for what we are doing, a recognition of a sector of theatre I identify with. Franco Quadri and the jury showed that they want to support and believe in new languages. There are very talented groups in Italy working with enthusiasm and optimism. The Ubu restores prestige to theatre, despite the difficult reality we are living in.”

A graduate of the Alessandra Galante Garrone Theatre School in Bologna, Francesca is now a two-time Ubu Award winner. In the 2004/2005 season, she won Best Supporting Actress for her portrayal of Aqua Marina. She dedicates this recognition to her mentor, Leo de Bernardinis, as she explains, a native of Cremona and now based in Bologna:

“In Aqua Marina, there is a tribute to Leo and to Ophelia (her first Shakespearean role) with a reference to the blind flower girl in City Lights, and to Totò, Prince of Denmark, (a text directed by de Bernardinis in 1990). I considered it an award to a piece of theatre history.”

For her portrayal of Ophelia, the Flower Girl, she was nominated as Best Actress for the 1990/1991 theatre season in the Patalogo Italian Theatre Yearbook by Gianni Manzella. She was also cited in the 1994/1995 theatre season by Giorgio Sebastiano Brizio, Renata Molinari, and Franco Quadri for her role as Donna Evira in The Return of Scaramouche and in the 1997/1998 season by Titti Danese for her role as Tina Modotti in Duetti Guerriglieri. Her extensive and fruitful artistic experience with de Bernardinis and the members of the “Teatro di Leo” company earned her the Dams Award in 2004 and the Viviani Award in 2006 at the Benevento Festival.

For her performance in West, she received more votes than the other nominees (notably competing against Mariangela Melato in the same category). She also stood out for her roles in the project Shoot, Find the Treasure, Repeat, a dramaturgical creation by Mark Ravenhill, in which she performed in The Trojan Women and The Mother (by the Academy of Artifacts, directed by Fabrizio Mercuri), which won the 2010 Critic’s Award. In March of this year, she also debuted in Intolerance.

“This project is important and very beautiful for my career. My encounter with Fabrizio Arcuri has been a fortunate one, the culmination of a relationship and an idea tailor-made for me. The satisfaction I feel at this moment is immense and brings me great pleasure. It is also because I am aware that I am working in a sector of theatre that is constantly at risk of survival. The Ubu is a prestigious recognition that encourages us to move forward,” explains the actress after the award ceremony, “aware that the economic crisis is widespread, but we are trained to resist and to produce with limited resources. I come from a school where you put everything you want into the work, but in the end, what remains is the actor and their performance – that is the most important thing.”

Her extensive curriculum shows that her theatre work is always driven by the search for new forms of expression, never yielding to routine. Was it a difficult choice to pursue a more demanding genre rather than lighter, more entertaining theatre?

“Thirty years of career have allowed me to always go on stage with something different. A continuous challenge, like in West, where there is no material time, no control over tone, volume, or positioning under the light. There’s no time for anything; it’s time you don’t have. You have to rely only on your craft.” This production achieved such success that in Milan, they performed eight sold-out shows. “The text is very personal to us. It talks about conditioning and our conditioned freedom. It is built on a dramaturgy that includes gestures, which also influence the audience.”

Fresh off her time in Rome, where she performed The Trojan Women and Intolerance with the company “Accademia degli Artefatti,” she is about to depart for Genoa to perform some of the Ravenhill project titles at the Teatro della Tosse (a theatre directed by Fabrizio Arcuri).

Do you also have time for other projects?

“I’m also working on a text by Pierre Notte, a very prominent French author abroad, journalist, poet, novelist, actor, and director. With Angela Malfitano, we are staging Deux petites dames vers le nord (Two Old Ladies Heading North), which tells the story of two elderly sisters who decide to travel north in their country to scatter their mother’s ashes. It’s a chaotic journey, a sort of road movie. We will bring it to Milan in February 2011 at the Teatro Oscar and in April to San Lazzaro at the ITC Theatre (Bologna), as part of the Parole di Francia initiative, sponsored by the French Academy, which involves an exchange of playwrights, with Italian authors represented abroad and French authors, like Pierre Notte, participating in Italy. I will also dedicate myself to a very interesting project by Pietro Babina, who wrote Eco, where the audience can follow the rehearsals and the building of the show online.”

Since 2003, she has been the artistic director of the Sguardi season at the Sala Teatro “Biagi D’Antona” in Castel Maggiore (Bologna), where she also focuses on theatre with a social direction.

“I work on projects involving various types of women. I run workshops to motivate women’s involvement in politics, a growing problem as more women are leaving it. There are fewer and fewer women in political careers. I also work with unemployed women and have visited women’s prisons to support their conditions. This aspect of my work is very stimulating.”

Francesca Mazza’s Dorothy Seduces the Elite of Theater Critics. She Wins the Ubu Award for Best Actress of 2010, by Vincenzo Branà, L’Informazione, December 14, 2010

It must be quite difficult to hide such a great emotion as winning the Ubu Award with just your voice. Francesca Mazza, yesterday, when answering the phone to those who insistently asked, “Is it true???” almost tried to mask her joy, aiming to keep the suspense intact until the official announcement later that evening on the stage of the Piccolo Theater in Milan. But then the sparkling tone and the occasional faltering vowels inevitably betrayed the secret: the fifty-three leading Italian theater critics had chosen her as the best leading actress of the year for her role in West, a play by the Fanny & Alexander company from Romagna, which premiered last June at the Festival delle Colline Torinesi. “I haven’t slept for four days and I’m getting teary easily,” the actress confesses once the secrecy is broken. “I’m overwhelmed with emotion and happiness,” she adds.

When the verdict was announced, she recalls, “I immediately thought of this play. It is particularly significant for me that the award comes with this production and with Fanny & Alexander.” The partnership between the actress—born in Cremona but a long-time resident of Bologna since her university days—and the Ravenna-based company truly seems magical. In fact, Mazza had already won an Ubu Award in 2005 as best supporting actress for the play Aqua Marina, also by Fanny & Alexander. Last night, however, the award came thanks to West, the latest chapter in O-Z, the Fanny & Alexander project based on Frank Baum’s story. “It’s a very particular play,” Mazza explains, “one that resonates with the audience, one that strikes. And it restores the meaning of doing theater at a certain level.” The downside is that, as of now, West is scheduled to only play in Bologna for two performances, on March 9 and 10, at Teatri di Vita.

The Ubu to Francesca Mazza. Theater Speaks Cremonese, by Nicola Arrigoni, La Provincia, December 15, 2010

Francesca Mazza, a native of Cremona, has tear-filled eyes. On Monday night, she was awarded the Ubu for Best Actress 2010 at the Piccolo Teatro for her role in West by Fanny & Alexander. With her red hair, light eyes, and petite physique, Francesca Mazza couldn’t believe it. Surrounded by Luigi de Angelis and Chiara Lagani, the founders of Fanny & Alexander, with whom she has worked for years—her “boys,” as she calls them—there were also Enzo Vetrano and Stefano Randisi, lifelong friends and extraordinary companions in the theatrical journey with the unforgettable Leo de Bernardinis.

Past and present were there to celebrate Francesca Mazza, who on Monday night—during a delightful and festive awards ceremony hosted by Gioele Dix in fine form—gave a powerful display of theatrical ethics, showcasing her authenticity as an actress committed to contemporary thought.

The 33rd edition of what is, in effect, the Italian theater’s Oscar, created by critic Franco Quadri and supported by the work of Patalogo’s editors and the publishing house Ubulibri, will be remembered as the edition that awarded Roberto Saviano as the “illegal” theater figure, absent from the Piccolo for security reasons and represented by Serena Sinigaglia, director of the play La bellezza e l’inferno. But the 2010 edition will also be remembered as the one that awarded three shows as the best of the year: Finale di partita by Massimo Castri, L’ingegner Gadda va alla guerra by Fabrizio Gifuni (who also won Best Actor), and Roman e il suo cucciolo by Alessandro Gassman.

The sense of theater as a civic act, a form of democratic resistance, marked the award ceremony. This was a commitment that Francesca Mazza embodied with great emotion when receiving the prestigious award. “I owe this prize to the intelligence and genius of Luigi de Angelis and Chiara Lagani,” she said. “West is not just a play; it’s the story of something that concerns and touches us all, it’s about the possibility we have to live and manage our freedom. The Fanny & Alexander team has extraordinary intelligence; they have a unique ability to transform ideas and read our present through the art of the stage, where the actor is part of a whole made up of words, sounds, and the relationship with space. That’s what happens to me in this journey to the West. In West, in front of the audience, I follow the different orders of de Angelis and Lagani each evening, testing myself, sharing a constantly evolving stage alphabet that speaks about the freedom to be and to live. My first encounter with theater was in the parish hall of my hometown in Cremona, and my first real play was here at the Piccolo Theater. That’s why receiving the Ubu here is an indescribable emotion.”

The applause from the crowded audience of critics, actors, actresses, and directors was long and sustained, as it should be.

Once the lights dimmed, the actress from Cremona confided: “I’m on cloud nine,” and the hug became stronger and stronger. “Now I hope to bring West to Cremona, maybe by the Po River next summer and then… long live Cremona.” One can’t help but feel proud of this fellow citizen, now a naturalized Bolognese and a globally recognized actress who has earned the Ubu as Best Actress in the 2009/2010 season.

Another Cremonese, Guido Buganza, a brilliant set designer, narrowly missed the coveted recognition by a few votes but will surely try again.

O-Z WEST by Fanny & Alexander at Angelo Mai, by Tiziana Cusmà, Rubric, www.rubric.it, February 7, 2011

What is WEST? A place, a direction, a condition?

Perhaps a bit of all of this, but it definitely represents the final chapter of a study on The Wizard of Oz, revisited and staged by Fanny & Alexander.

But be warned: this is not the Wizard of Oz we are familiar with, so don’t think of Dorothy from Baum’s novel.

Here, we find a woman (Francesca Mazza) sitting on a chair, leaning on a small table at the center of the stage. A long braid frames her face, and her red rhinestone shoes contrast with the green dress hidden beneath her jeans and t-shirt. She tells us, “I’m Dorothy and I’m 52 years old.”

The perimeter of the stage is marked by a white ribbon, almost forming a ring; at all four sides, there are spotlights that never change color or intensity, casting a cold, detached, naked light.

The actress taps her fingers on the surface of the table, moves her legs, and draws unusual geometries on the floor with her red shoes. A strange choreography of tics, gestures, questions, and intense sounds begins, and it seems clear that these are the first signs of disturbance.

Starting from the idea of a strange experiment conducted on a group of volunteers, the play presents the torment of a victim of the persuasive power of communication, embodied in a Dorothy of our times who is increasingly confused, trapped, and confined by the incessant suggestions of two unseen persuaders—Marco Cavalcoli and Chiara Lagani’s off-stage voices—crushed by a language she no longer controls, as if enchanted by a spell that hinders her agency.

Thus, the play unfolds: the actress fights alone on stage, seized by continuous shudders, neurotic gestures, and words that repeat in cycles; a repetitive, stereotyped, but absolutely perfect gestural language, meticulously detailed, as is her precise and communicative facial expression.

Dorothy is a woman, in some ways moving, in her submission to a diabolical and perverse game made of subliminal persuasion texts. The inputs she receives through her earpiece give her different commands: one tied to a series of gestural clichés, the other to a sequence of textual frames that, when combined differently, create a script.

As the gestural and verbal score progresses, it becomes increasingly fragmented, more neurotic, disturbing, contaminated, desperate, making the words fail to define anything. A barrage of commands and impulses that could induce obsessive neurosis in anyone. A deafening repetition designed to condition the human mind. At times, it feels like entering a trance. The psyche is twisted, risking a dangerous state of alienation. The tension in the air is palpable. Words cross, confuse, accelerate, and reverse in meaning.

A show that captivates, hypnotizes, and sucks you in, but at the same time reflects and makes you reflect on the twists of contemporary imagination and the individual’s role in society.

A great round of applause and admiration goes to actress Francesca Mazza, intense and the medium through which this entire journey unfolds, an extraordinary performer of this crazy and enchanting directorial score. Excellent.

The entire theater program at Angelo Mai should be kept an eye on, with performances by Accademia degli Artefatti, Motus, and Federica Santoro, among others.

Dorothy Prisoner of Images, by Alessandra Bernocco, Europa, March 9, 2011

“I’m Dorothy and I’m fifty-two years old.” This is the first line of an acting performance we haven’t seen in a long time. It is delivered by Francesca Mazza, the sole performer in West, the final chapter of a tetralogy inspired by the story of The Wizard of Oz, which earned her the 2010 Ubu Award for Best Actress.

Conceived by Chiara Lagani and Luigi de Angelis, the two founders of the twenty-year-old Ravenna-based company Fanny & Alexander, West represents the extreme end of a journey where the protagonist touches the four cardinal points.

Just like the young Dorothy from L. Frank Baum’s novel, who in the land of Oz encounters two good witches and two evil witches, the journey of this 52-year-old Dorothy, with her red shoes and long braid falling over her shoulder, is no less difficult and exposed to trials.

She receives orders from two different voices, one male and one female, transmitted through two microphones, which urgently instruct her to perform a series of tasks without reflection. These are verbal and gestural actions, intertwined, overlapped, and embedded in a tight, relentless score that offers no respite, even for the audience.

It is a “frenzied” reflection and denunciation of the subliminal mechanisms of manipulation by advertising language, which imposes its repertoire of quotations, repetitions, and hidden persuasions. The actress exposes this like an automaton. Everything in her is obsessive, even grace, even sensuality. The obsessive looks, the repeated falls, the exacting gestures according to a precise, unchanging instruction. The obsessive itching and the swaying of her leg, the controlled energy, the minimal, rhythmic, suggestive gestures, the symmetrical walk around the four sides of the stage.

Trapped in a non-thought that hinders her judgment and decision-making, Dorothy expresses herself through a nonsignificant flow of movements and words. Her only supports on stage are a small table and a chair: they are the points of reference she starts from and returns to in a symbolic cycle that has no break. The times of this journey, between myth and our sick contemporary reality, are punctuated by the unsettling sounds of Mirto Baliani’s DJ-set.

With Francesca Mazza, the present is a sentence

By Nicola Arrigoni, La Provincia, July 27, 2011

What is West? How to interpret Francesca Mazza’s performance as a supermarionette in the style of Mejerchold, at the mercy of Marco Cavalcoli and Chiara Lagani from Fanny & Alexander? Is it a display of virtuosity, excellent acting technique, or something more: a sign of a condition that is both aesthetic in theatre and existential in life? These are the questions raised and imposed by West, which was seen at Ronchetto, at the opening of the Il Grande Fiume festival, in front of a packed and applauding audience.

The outcome is, in the end, a long, interminable applause for Francesca Mazza, the actress who executes the vocal and mimetic score suggested by the two “hidden persuaders” at the back of the room, accompanied by Mirto Baliani’s DJ set. One wonders if the actress’s skill alone is enough to make the show convincing, even though her performance earned her the Ubu Award 2010 for Best Actress. What happens on stage? This: Francesca Mazza is body and soul at the mercy of hidden persuaders, she is Dorothy, a 53-year-old woman who lacks the courage to say no, who wishes to be rejected out of a desire to exist, perhaps longing to experience the exceptionality of love but ending up settling for the normality of affection. Like a dog. Dorothy’s horizon is the perpetual present; it’s saying yes and wanting to learn to say “no,” it’s the utopia of autonomy and the awareness expressed in the line: “I am here and I cannot do anything else.” Dorothy— the character from The Wizard of Oz upon which West is based—is a presence controlled by others, by hidden persuaders and, as suggested by Fanny & Alexander, by the subliminal messages of advertising: “image is zero, satisfy your thirst,” or by our belonging to the culture of the West, symbolized by America and its stars and stripes. All this happens with a slow and obsessive intensification of rhythm and situations that Francesca Mazza is tasked to execute: small and syncopated nervous gestures performed in unison with a dramatic score suggested by a male and female voice, voices that at times make themselves ‘visible’ to involve the audience in the sacrificial game the performer submits to. The result is the mounting sense of ‘constraint’ on one hand, and awe for Francesca Mazza’s interpretive flexibility, as she bends traditional acting to a disorienting and alienating context, creating an interesting aesthetic short circuit. And then? In the end, the awareness remains that West, the West, is nothing but an impossible horizon, an unreachable place, not just or only America or a critique of a consumer society, because the horizon is more dramatic: it is the absence of an horizon, the condition of existing without the possibility of being. In all this, one senses the boredom of an existential situation with no way out, a situation that can only repeat itself endlessly, perhaps growing in intensity but certainly not changing, until the anguishing and eternal question arises: “Wouldn’t we have a better life, if we had the freedom of choice?”

Listen to Your Thirst,

By Pietro Piva, Gagarin – Orbite Culturali, November 2011

We open this month with West by Fanny & Alexander. It will be performed at the Artificierie Almagià from November 24 to 26. This show earned the lead actress, Francesca Mazza, the Ubu Award for Best Actress in 2010.

West is part of a large project, the OZ Project, through which the Ravenna-based company draws from Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, creating a mythical and prolific imaginary, almost with an archetypal approach. The novel becomes a lens, a classic, an opportunity to read the contemporary. Many shows stem from this project: EAST, Emerald City, KANSAS, HIM, Dorothy: Disconcerting for Oz, and West. We saw this work at the Ipercorpo festival in Forlì, so it will be interesting to discuss it without revealing the theatrical trick.

The program flyer is shaped like a remote control. The buttons feature commands related to the timeline and emotions. It quickly becomes clear that we are dealing with some form of control. Commands are being given to us, or perhaps we are giving them. The suggestion is that we are part of a large machine, and it’s hard to say if we are driving it or if we are even on stage ourselves. The sound suggests a mechanism, a mechanical rhythm. The dynamics of the show are like a car preparing for a long journey, from starting the engine to racing down the wrong highway. The gesture. The chosen gesture. The perfect gesture that betrays itself, that trips. The hidden persuader-director becomes a vocalist for the occasion: he orders, proposes, from the console. Induces needs: he is the syringe of Beckett’s God Prodding, waking the man, anesthetizing the man. “Listen to your thirst” is his definitive manifesto, the table set and branded by the Law. The jingle becomes imperative in the wild west. And then your personal fragilities, your weaknesses, are forever out of place. You are embarrassing and inappropriate. They magnify, becoming immorality to repress until suffocated. The West, in the sign of guilt, uses and throws away our particular memory.

Another story is the craft that presides over this show. The technical question is worth mentioning for once. It’s an intelligent and shared theatrical research methodology with the audience in real time. It’s like mirroring the images emitted by this work: we’ve already discussed gesture, for example. It’s a chosen gesture, skilled, brought to the point of excess. It too pertains to some form of control, but one that gradually leads to abandonment of self, to the unknown. The craft of this show is control that is not control. It goes wherever it wants because it allows itself to let everything go, and the work of an actress who takes nothing for granted, who listens to herself in delirium, tearing apart the Great Mechanical Score from within.

Theatre is given. The case is given that the small and petty biographical experience from within becomes universal beyond the fourth wall.

West, Francesca Mazza and the Allure of a Choice

By Jimmy Milanese, Franz, www.franzmagazine.com, February 2, 2012

Why not push further? If we want to save people, why not take away their freedom of choice?

Francesca Mazza, a talented actress who has made Bologna her home, places herself at the center of the stage, stripping away all the masks that have encased Western society—the “West.” She confronts us with a complex paradox: the inherent injustice within the very possibility of choice.

In an hour of intense monologue, radio-guided by a mysterious external source—representing the process of conditioning acting on the human being—Francesca succeeds in sabotaging the buried unconscious of the audience, who faints, leaves the room, or feels a sense of disorientation, if not terror. The prolonged and liberating applause from the large crowd present in the theater closes the dangerous black hole opened by the theater group Fanny & Alexander, avant-garde artists in an era where it seems almost impossible to astonish, captivate, or move with minimal resources.

There are no naked bodies, exposed breasts, no stories of violence, blood, or social degradation; there is not the slightest hint of an unexpected twist. Everything is linear: a chair placed inside a ring marked by a simple strip of tape. In front of that chair, occupied by the only protagonist, is a table, illuminated by four powerful spotlights placed at the corners of the square. Four lights and four dimensions that interact to alter an emotional, psycho-physical, and cultural state! Two off-stage voices, one female and one male: one guiding Eros and the other guiding Thanatos (the life drive and the death drive). In the center of the stage, a 52-year-old girl, freshly emerged from the wonderful world of Oz. She exits, we enter, but we don’t find enchanted landscapes or picturesque characters that remind us of our childhood. In Dorothy’s world, there is our atavistic cultural experience, with its hidden persuasions, the conditioning that has seeped into the nuances of our neuroses, which have smoothed our personalities, leading us to the sublime illusion. We can choose, it’s true, but only between “black and white,” “right or left,” “I like it or I don’t like it,” “life or death.” Our range of choice is the product of a binary choice, much like the binary world of computing, which now governs and marks our lives. For this reason, Western societies have constructed the concept of “destiny,” gifting us with prepaid cards, life insurance in case of death, thirty-year mortgages, marriages, and nursing homes next to kindergartens.

Therefore, the illusion of democracy lies in the allure of that choice, between “A” and “not-A”: a fictitious, artificial choice, lacking the main component of F-R-E-E-D-O-M. The possibility of non-choice, or of an intermediate option; the possibility of denying the rules of the game and, in the extreme, expressing no preference. Those who align with this side are often called “crazy,” or “artists.”

West, A Journey Through the Imaginary

By Loredana Borrelli, Teatro.org, April 17, 2012

An essential and neutral stage space, a non-place at the edge of the imaginary, a wooden table, an aseptic atmosphere, black walls, and at the center, as if she had been thrown there by chance, a woman with her glittering red shoes.

Her body is the first to speak, moving nervously with rhythmic and measured gestures. She explores the space around her, which she seems to be imprisoned in… “My name is Dorothy, and I am fifty-two years old,” are her first words. However, her identity seems forgotten. Dorothy repeats this phrase in an attempt to recognize herself, to find herself within a world focused on a form of hidden persuasion that leads to disorientation. The black room where she moves and responds to the gestural and verbal commands of two inquisitors (internal?), is a space at the boundary between the real and the imaginary, where she is stripped of all her certainties, almost losing touch with her own body.

The body and voice, exacerbated, alienated, sought after, are the engine through which the character Dorothy takes us on a journey inside herself, making us unsuspecting companions and spectators on a path through her soul and memories, partially shaped and conditioned by an unsettling language of advertising.

The work done by the group founded in Ravenna by Luigi De Angelis and Chiara Lagani, inspired by The Wizard of Oz, is deep and evocative. The choice of the “most out-of-fashion character” serves as a provocative and irreverent act. The most out-of-fashion character is Dorothy herself, who encapsulates, in potential, what each of us could become if we completely abandoned ourselves to the paradoxes of reality. The most out-of-fashion character could be any one of us.

West, or the Death of the Image According to Fanny & Alexander

By Giulia Tirelli, iltamburodikattrin.com, August 2012

Dorothy is 52 years old. She sits, tapping her long fingers on a wooden table or on her chest. In silence. She is enclosed within a square enclosure, marked by white adhesive tape. Dorothy is no longer the young girl swept away by a tornado into the fabulous land of Oz. There are no scarecrows, tin men, or lions accompanying her on her journey. Dorothy is alone, abandoned to an experiment where her mind is being conditioned by the sound of two different voices.

With West, Chiara Lagani and Luigi de Angelis close their cycle inspired by L. Frank Baum’s masterpiece, bringing to life an immaterial world entirely based on a mechanism of psychological induction—masterfully orchestrated by Marco Cavalcoli and Chiara Lagani with DJ sets by Mirto Baliani—that creates subtle plots and networks which trap the audience in a magnetic field of gestures, music, and words. The resulting score ensnares the audience in what appears to be an experiment in collective hypnosis, triangulated by a sublime Francesca Mazza, who delivers a solo of movements and broken phrases.

The scene, stripped of any embellishment, transforms into a mutable fabric, a magma where it’s impossible to establish reference points. The audience is drawn into a vortex where dramaturgy and action seem to chase each other in search of an unattainable unity and harmony, barely touched by the overlapping personalities that take over the performer, dressing them like a mannequin. No preordained text, music, or gesture, no narrative line guides the audience, leading them by the hand. The only engine of the performance is Dorothy’s body, symbolizing a broken psyche, severely compromised by a world that imposes behaviors and norms through a mechanism of tight stimulus-response, from which there is no escape.

In West, the cancellation of the image becomes a structural element used to build a mental cage that must be dissected. The scene transforms into a metaphorical glass case constantly illuminated, within which the subject is subjected to an experiment that escapes the boundary of the white tape and projects itself onto the spectators, erasing the distance between the stage and the audience. We thus find ourselves as both victims and perpetrators at the same time, in a continuous shift of perspectives that causes all cardinal references to be lost.